By Sonia Corrêa

A few days before completing the symbolic mark of Jair Messias Bolsonaro’s – or JMB’s – first 100 days of government, consecrated in western democracies as the first moment of fair evaluation for a beginning administration, JMB said that he was not born to be president, but rather to be a military man. “It’s just one problem after another“, he said, after being questioned. “I ask myself, I look to God and I ask: ‘My God, what did I do to deserve this?’”. Although intended to be ironic, JMB’s words should be taken seriously, as their content was reiterated by the President in an interview granted to Revista Veja at the end of May. They condense JMB’s rhetorical style, so dear to his constituents, in which he “says what he thinks without so much as a blink”. They also reflect the cacophony of the early months of his administration.

Since January, the government scene in Brazil has been marked by sequential clashes between the various groups that are in power today: the president and his three sons (who are generally guided by the diatribes of the astrologer-cum-guru Olavo de Carvalho, comfortably settled in Virginia)[i]; the eight military ministers; the voluble economic minister Paulo Guedes; and the conflicted government base in Congress. Serious signs of administrative incompetence overlap with an avalanche of executive acts that, with or without legal basis, are altering public policy parameters in a wide range of domains. There has also been the systematic use of Twitter to “rule” and stir up the bellicosity of the government’s loyal electoral base. Arbitrary or messianic declarations and grotesque or ridiculous scenes are staged every other day by the president and his ministers. Some observers have even drawn attention to how the presidential behavior demonstrates signs of political bipolarity. During the day, perhaps through the influence of the military and other more rational and calculating ministers, JMB sometimes behaves reasonably. But at night, when he returns to Twitter, furious, he becomes Bolso-Nero.[ii]

An important group of critical analysts has devoted themselves to discern what lies behind the sand and garbage storm that this cacophony produces (listen here). Journalist Eliane Brum, in a beautiful and balanced article about the first hundred days of the administration, described the Bolsonaro regime as a government that is opposed to itself, emphasizing that this is not casual and that, above all, it produces distraction and paralysis. In a similar vein, Marcos Nobre, in an analysis published by Revista Piauí, analyzed how this chaos is not accidental or a symptom of the ignorance and unpreparedness that actually exist. According to Nobre, chaos is a method of government because:

… the only way for Bolsonaro to secure himself in power is to actively keep the country’s political institutions in a state of collapse, the same state that led to his election… The hardcore loyalty that has been with him since the beginning depends on maintaining institutional collapse.

The other face of chaos is, therefore, bellicosity. Since January, presidential decrees and other executive measures have proliferated that change programs and policies in the most diverse areas while cutting resources. JMB explained this mode of management recently by saying that with a pen in hand he has more power than the president of the Federal Chamber. There have been numerous presidential decrees since January, including two that increase accessibility to firearms in Brazil and a more recent one that reduces fines for traffic infractions. The pen has been applied mercilessly and arbitrarily, especially in areas where the government wants to show its ideological point of view, or where there is greater potential for resistance. Among the many measures that have been enacted are those that: control civil society organizations, dismantle social participation mechanisms, eliminate rules of environmental protection, alter the organization chart of the Ministry of Health, and impose a drastic reduction of resources for public universities.

This last measure had great visibility and was widely criticized internationally (see a compilation). It is worth remembering, however, that not only universities are under attack. When this balance of the first 100 days of government was being completed in June, the three largest public data production institutions that inform national public policies were under attack. The IBGE was subject to intervention and had its resources for the 2020 Census reduced. FIOCRUZ was prevented by the Minister of Citizenship from publishing a national survey on drug use, the results of which contradict Bolsonaro’s criminalization agenda and its call for compulsory government rehabilitation. Finally, the Minister of the Environment threatened to replace INPE, which had just released data on the increasing deforestation of the Amazon by private companies.[iii] This anti-intellectual crusade replicates what is seen in other contexts now ruled by right-wing populists, inevitably evoking fascism.

It is therefore not surprising that several of these executive measures do not have a solid legal basis. They have been and will be questioned judicially. Lawyer Eloisa Machado recently analyzed the decree transferring the appointment of sub-rectors of public universities from rectors to the President of the Republic, claiming that it openly violates the constitutional definition of university autonomy. She concludes that:

A government based on decrees and provisional measures shows its incapacity to establish a dialogue with and form a base in the National Congress, exposing itself to the scrutiny of parliamentarians and of society. The shortcut the government has found to escape the costs of political negotiations is to abuse power … We are now facing an unconstitutional government.

In an article published in Folha de São Paulo, philosopher Vladimir Safatle observed that permanent war is needed in order to sustain the loyalty of JMB’s electoral base and to implement, systematically, the conservative revolution he embodies. This means a persistent and fierce struggle against the political caste, the judiciary, the press, and the intellectual elite. This dual role was blatantly on display in the May 26 rallies called to support the government’s priorities (and which included JMB’s personal twitter appeals for support) – pension reform and the anticrime package – but that also implied attacks against the Supreme Court, the Congress and their leaders. The tragic irony of what is underway is that, as Safatle rightly points out, this “revolution” is giving the country over to those who have always been its owners: “the bankers with their unbelievable profits in a paralyzed economy, entrepreneurs who plunder workers, rentiers who have their incomes untouched“.

Eliane Brum was, therefore, very perceptive when, in her April article, she invoked an image of the “government of the perverse” to name the extreme conditions of abnormality, uproar, and occlusion of the first hundred days of the JMB government. Brum uses two different angles to explore the markedly perverse traces of a political scene, which, on the surface, seems to be simple misrule. On the one hand, she examines how the cacophony and political bellicosity of the first months of government have obscured and normalized the tacit authorization of the killing of Brazil’s most vulnerable. This is a carnage caused by the collapse of the public health system and, above all, the persistent lethal effects of structural violence, which includes an increasing number of lethal victims of state violence or omission (read here). In the state of Rio alone, in the first six months of 2019, 434 people were executed by the police, including a singer and homeless who were shot by an army patrol. We have also witnessed brutal rebellions and massacres in prisons: at the end of May, 55 people were executed in a dispute between factions in a prison in Manaus, but this tragic event did not garnish much attention from the President or his Justice Minister.

Brum also calls attention to the bewildering impact that a government that behaves as opposition to itself has on the forces that could and should oppose it. Above all she describes with great skill the perverse fascination that the current political scene is exerting on society:

Both the opposition and the press, as well as organized civil society and even a large part of the population, are living according to the rhythm of the calculated spasms that Bolsonarism injects in our daily lives… We are under the yoke of the wicked, who corrupt the power they have received through the vote in order to impede the exercise of democracy. Since the state machine is in their hands, they can control the agenda: not only that of the country but also the themes of the daily conversations of Brazilians, over lunch or at the coffee machine or even at the bar. What will Bolsonaro do today? What will the bolsojuniors say on social media? What will be the new delusion of the bolsochanceler? Who will the bolsoguru attack this time? What will be the bolsopolemic of the day? This has been the country’s agenda.

This painful description evokes the voyeuristic effects of Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last film, in which the cynical, exhibitionist, sadistic traits of fascism as a manifestation of power are eviscerated in brutal and repulsive images from which, however, we cannot force away our eyes. This association is even more pertinent when “sex”, toxic masculinity, tropes of sexual domination, and gender-based attacks are at the forefront of the national scene. As I have pointed out in previous analytical essays, gender and sexuality have long been in the hurricane winds of the conservative restoration that swept Brazilian politics to the right in the 2018 elections. But the coming to power of the forces that propelled this storm makes it literally impossible not to talk about sex when writing or talking about politics in Brazil.

A profusion of declarations, gestures, tropes and symbols regarding gender, sexuality, and abortion have proliferated in the Brazilian political semiosphere since January and there are multiple sources that propagate this intense discourse. A number of figures occupy this pantheon. One of them is Damares Alves, who heads the newly created Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, and is known worldwide for saying in her inaugural speech that boys should wear blue and girls pink and for radically repudiating the right to abortion at the various international meetings in which she has participated. Another voice is Ernesto Araújo, Minister of Foreign Relations who, in previous writings, has affirmed that feminists aim to criminalize male sexual desire. The newly appointed Minister of Education has contributed to this flow when he said he would cut off the resources of three public universities that promote “uproar”, imparting a strong sexual connotation to the term.[iv]

However, this is a domain of semantic politics in which JMB and his astrologer-cum-guru, Olavo de Carvalho, are unbeatable. The cornucopia of profanities that the astrologer uses in his writings and apparitions on Youtube is now a factual datum of the Brazilian political reality. The title of a long text, published in Ilustríssima authored by philosopher Rui Fausto to contest Carvalho’s unusual theses is “The only rigorous thing in the writings of Olavo de Carvalho is the profanity”. In another very ironic article published in The Intercept, Mario Magalhães does a fairly complete exegesis of Carvalho’s obsession with “assholes”, especially those of other people, to conclude that:

The obsession with the rectums of others is not behavior worthy of moral consideration, but a mystery of Carvalho’s soul. It expresses itself against the usual suspects: “When a Brazilian leftist calls you fascist, he does not mean that you defended some fascist idea. He just wants to say, “Oh, my asshole hurts.”

Even so JMB is not very far away from his guru in that respect. For many years he has reliably generated gender and sex topics in his political declarations. But now he has a gigantic illuminated stage upon which to spread his “sexual” tropes and gestures with new contours, greater intensity, and more impact.[v] Several times, since his election, including during his trip to the U.S., JMB has made statements declaring his “heterosexual love” for the men who surround him, especially Minister of Economics Paulo Guedes (transforming the ultraliberal project in progress into a work of alpha males who “love each other”). During Carnival, JMB posted a “golden shower” scene on his Twitter feed, claiming to abhor it (read here). This extreme gesture – which mixes homophobia, repulsion towards sex, and promotion of moral panic (which incites hatred) – quickly found its way into the international news. The President then went through what Naief Haddad calls “a candid obsession with the penis”. In April, JMB made a comment about penile amputation caused by lack of hygiene, proposing public campaigns to teach boys to always wash their genitals, similar to campaigns the military currently promotes. He then made several declarations regarding penis sizes, evoking, as he always does in Brazil, the sexual organs of the Japanese. He made a joke about this when he was approached by a Japanese tourist in Manaus. Shortly afterward, he used the “little Japanese” metaphor to comment on the possible results of the pension reform bill.

This vertiginous sequence of speech acts and sexual gestures culminated in the first week of June with two episodes of extreme misogyny. A week after the massacre at the Manaus prison – which was not the subject of any solid comment or attitude on the part of the President or his Minister of Justice – JMB dedicated a whole paragraph of commentary on Twitter to mourn the suicide of MC Reaça, author of a jingle in his presidential campaign, whose aggressive lyrics offend all of JMB’s opponents and calls feminists bitches. MC Reaça killed himself after beating his pregnant lover. A week later, when the soccer player Neymar was accused by a girlfriend of non-consensual sexual intercourse, the President visited him at the hospital, where the soccer star was recovering from an injury, in order to provide him with solidarity and to raise suspicions about the intentions of the woman who raised the charges.

So far, JMB, in fact, has not yet signed any prohibitive decree regarding gender and sexuality. But in a televised scene, flanked by two generals, he urged parents to tear out the pages of an HIV prevention primer (published by the Ministry of Health) which includes female and anatomical images. While it is very hard to predict what comes next in Brazilian politics at large, it is flagrantly easy to say that JMB does not lack the will to try and arbitrarily discipline the sex life of Brazilians. As we shall see, this will is permeating, albeit not always in a transparent manner, measures that have been adopted in various areas of his administration.

Translation: Thaddeus Blanquette

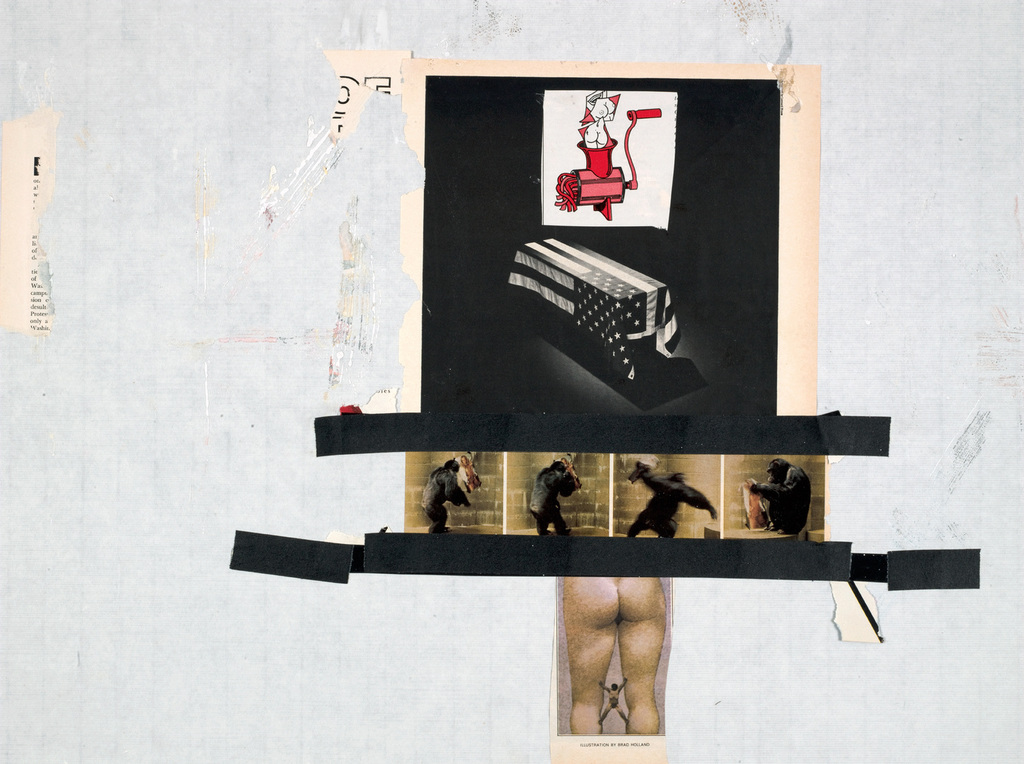

Image: Domestic devices 4, by Chilean artist Katia Sepúlveda.

Notes

[i] Olavo de Carvalho is an astrologer and self-proclaimed philosopher who, for two decades, has expressed extremely conservative political views (mostly borrowed from European conservative Catholic thinkers) on all matters. He has been self-exiled in the US since 2005, declaring he was fleeing the dictatorship imposed upon Brazil by the Lula government. Very influential in social networks, for some years now he has functioned as the political counselor of the Bolsonaro family. To learn more about Carvalho read here.

[ii] This analysis is available in Portuguese in issue #52 of Podcast Forum Teresina at Revista Piauí.

[iii] FIOCRUZ is a century-old and internationally acknowledged public health research institution. INPE, the National Institute of Space Research, is a public institution devoted to scientific research and satellite mapping.

[iv] This declaration is what inspired the title of this essay.

[v] The international press has extensively reported on Bolsonaro’s misogynous and homophobic parlance since the early days of his political career. When he was elected, the feminist web magazine Gender in Numbers published data on these declarations, informing that since 2011, JMB has mentioned the term “gender ideology” 63 times in his speeches in the House and in his inauguration speech. The President’s commitment to combat “gender ideology” has also reached the international pages and screens. On June 2nd, the illustrated supplement of the Folha de São Paulo published an article by Naief Haddad that compiled the sexual declarations and gestures of the President, which can be accessed here.