By Massimo Prearo*

That words such as “revolution”, “change” or “turn” can be attributed to a religious institution like the Catholic Church, or to the words of a pope, says a lot, in my opinion, about the difficulty of placing the politics of gender, sexuality and family in a long-term perspective. This is especially the case in Italy, where it is still believed that political decisions around these matters are dictated by the Vatican’s booths of command.

Pope Francis’ position regarding same-sex civil unions revealed only on October 21, 2020 — but originally related and assembled in a 2019 documentary — and partially denied by the Vatican only a few days later, reaffirms the understanding that the Church and Catholics pertain to a secularized world, in which religion and doctrinal references are placed in the background or in a second level,– if this is really the case — as arguments or rhetorical expedients to be used only when necessary.

In other words, it is as if we were in a panting, tiring, and often ridiculous race to reposition the Church in the world, recalling that the first legal recognition of a homosexual couples’ marriage was in the Netherlands in 2001 and the last one in 2020 in Costa Rica. This race is not so much to influence political decisions (because it will be a little bit late for that), but rather to save what can still be saved from a secularized Catholic base, for which religious precepts are no longer equivalent to state laws and for which democratic principles of justice, freedom, and equality — or some more restrictive version of them — can no longer be sacrificed on the altar of “non-negotiable principles”.

In 2016, during the debates on civil unions in Italy, right-wing forces that opposed the bill often did so using “scientific” and “anthropological” non-religious arguments. In contrast, in the center-left camp, those who supported the proposition often relied on religious arguments and referred precisely to the figure of Pope Francis. But there is a more distant memory. In 2005, during the referendum to repeal Law 40 on assisted reproduction, the Vatican and the Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI) fought hard to maintain the law that it would be viewed by some as a “Catholic law”, because it accepted homologous fertilization, in the context of the couple, prohibiting heterologous fertilization, outside the couple.

The same applies to the first bills on the Anticipated Dispositions of Treatment (concerning palliative care and dignified death) which got some episcopal support, justified by the premise of the “lesser evil”. In other words, for the Catholic Church, it was better to establish a limit while it was feasible than to leave open the possibility for Courts or new political majorities to enlarge this loophole and which could, even further, lead to the acceptability of euthanasia. And let us not forget the “Franciscan” discourse on the pastoral care of abortion, which condemns it as an abominable sin, but extends a hand to the miserable sinner.

Very different, however, is the discourse of the new “pro-life”, anti-gender, and pro-family Catholic movement, nourished by intransigent doctrines and “natural” laws directly written by God upon the skin of humans and, above all, one can say, of women. Even so, when we look at it more closely, secularization has also affected this movement that now moves independently of Pope Francis’s declaration, of the positions of the Italian Conference of Bishops, or even of the ranks of marionette-bishops always ready to fulfill their duties.

But for the neo-Catholic movement, too, religious rhetoric is welcome, if necessary, to sustain an argument or a slogan. Otherwise, they will go forward alone — or well accompanied by the “secular” voices of Giorgia Meloni, Matteo Salvini, Maurizio Gasparri, Paola Binetti, Isabella Rauti, Lucio Malan, Simone Pillon, and company– towards what Senator Gaetano Quagliarello names as “anthropological Catholicism”. To illustrate this, it is enough to check Gasparri’s tweet with the photo of the smiling Massimo Gandolfini, leader of the Italian anti-gender and “pro-family” movement — which calls itself Family Day in English –, alongside leaders of center-right, right, and extreme-right parties, during an October 17, 2020, national demonstration against the bill proposed by Congressman Alessandro Zan (#ddlZan) that calls for criminalizing homotransfobia as hate speech.

In fact, it will be better to follow with these secular actors, since they are the ones who are now in the command booth of Parliament and have the possibility of manipulating the legislator’s pen to make him write a law that provides for the recognition of the union of two people of the same sex, but not the parental ties existing between this couple and their children.

This extraeclesiastic, extracatholic and intrapolitical positioning is what I have defined as “neocatholic” to name the politics of a movement that is new in relation to “traditional” Catholic forces. The neocatholic hypothesis is like a finger pointing to the moon, indicating it at the same time that it accuses it. That moon is the Church, the Pope, the Vatican and Catholicism. Let us thus discuss the pontiff’s lunar declarations, but without forgetting the finger pointed at it by the neocatholic movement that moves today in institutional spaces, while the pope smiles at journalists.

This article was originally published in Italian and was translated by SPW coordinator Sonia Corrêa.

These reflections are fully elaborated in the book L’ipotesi neocattolica. Politologia dei movimenti anti-gender (The Neocatholic Hypothesis. Politology of Anti-Gender Movements) written by the author and soon to be released.

*Massimo Prearo is a political scientist, member and scientific coordinator of the research center PoliTeSse – Politics and Theories of Sexuality at the University of Verona (Italy). He has already published in the field of LGBTQI+ movements studies: Le moment politique de l’homosexualité. Mouvements, identités et communautés en France (PUL, 2014) and La fabbrica dell’orgoglio. Una genealogia dei movimenti LGBT (Edizioni ETS, 2015). With Sara Garbagnoli, he co-authored La croisade anti-gender. Du Vatican aux manifs pour tous (Textuel, 2017, also available in Italian at Kaplan, 2018).

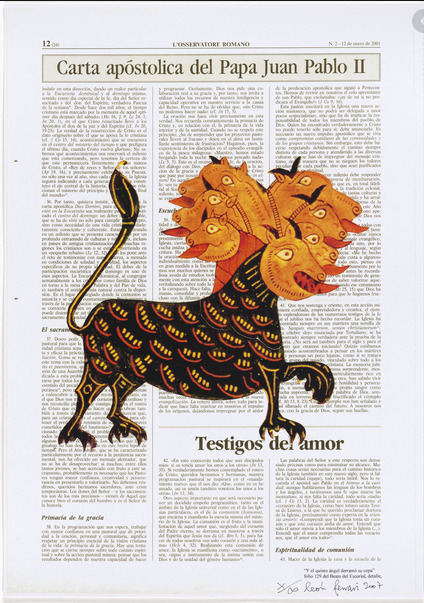

Image: Untitled from L’Osservatore Romano (The Roman Observer) 2000–01, León Ferrari.

L’Osservatore Romano makes reference to a traditional newspaper of the same name prepared by the Vatican whose directive was to counter calumnies against the Roman Pontificate. The Argentinean artist Léon Ferrari has as one of his main themes the criticism of the Catholic Church. Learn more about the artist.