By Sonia Corrêa

A new encyclical signed by Pope Francis I was published in early October 2020. Entitled Fratelli Tutti, the new papal exhortation was widely acclaimed by voices located across the political spectrum, as well as by the mainstream press. Two months later, in early December, a new policy platform established the Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican which gathers a significant and quite plural group of corporations and philanthropic institutions, such as the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations. Though these two facts certainly deserve much a deeper analysis, they are briefly mentioned here just to illustrate the hyperactivity of the Vatican in recent months at a quite peculiar political moment.

For example, an analysis of the newspaper El País, published at the end of November, reports that Francis, after creating 73 new cardinal posts, finally has control of the cardinal school that will elect his successor. Additionally, both the encyclical and the new Council for Inclusive Capitalism must also be situated in relation to the U.S. presidential election outcomes that gave victory to the first Catholic president since John Kennedy.

But that is not all. Amid the various eventful facts, on October 21, news broke that the Pope had made a declaration in favor of same-sex civil unions in the documentary Francesco, by Russian director Evgeny Afineevsky, shown at the Rome Film Festival. The news, as would be predictable, was widely and effusively received in the media and the LGBTTI and feminist activism camps.

Thirteen days later, however, the Vatican threw a bucket of cold water on this enthusiasm. It officially informed that the statement, recorded in the documentary, had been cited “out of context” and should not be read as a doctrinal inflection. By then, several media outlets had already revealed that the excerpt from the film, in which the Pope refers to civil union between same-sex persons, had edited responses to questions asked of the Pontiff at different times. More especially, these reports mentioned that following Francisco’s comment that “we need to create a law of civil union,” there was another phrase — “talking about same-sex marriage is something incongruous” — that was suppressed from the final edition. The Vatican’s corrective explanation suggests that the director had extrapolated the parameters established for the documentary by the Holy See’s Communications Office. But by that time, both the publicity for the documentary and another wave of the Pope’s popularity had been assured. In fact, ecclesial authorities would begin to reproduce the contested papal discourse, as was the case of Cardinal Carlos Aguiar, archbishop of Mexico City.

Commenting on this episode, the Italian political scientist Massimo Prearo published a note on Facebook that was later transformed into an article for SPW. In it, he examines the papal speech in light of Italian sexual politics, recalling that this is not the first time that papal interviews have both surprised and produced unusual effects. According to Prearo, what we saw in October was just another chapter of a breathless race to situate the church in an increasingly secularized world. Above all, Francis’ smiles for journalists and activists must always be situated in relation to the wider political context in which the neo-Catholic movement – widely engaged in crusades of opposition to abortion rights and gender – is at work without major constraints in the most varied institutional policy arenas and societies at large.

Another event that took place a few days after the Pope’s glaring speech on same-sex marriage became viral may sharply illustrate what Prearo means. On October 24th, a public webinar to debate Catholic perspectives on the 75 years of the UN System was sponsored by the Mission of the Holy See as a Permanent Observer at the UN in partnership with the Lumens Christi Institute, the Jesuit magazine America Media and the Kellogs Institute for Studies in International Relations. The two main speakers at the event were the head of the Vatican Mission at the UN, Archbishop and Ambassador Gabrielle Caccia, and the Harvard law professor Mary Ann Glendon. Glendon, as many may know, was the Vatican’s representative at the World Conference of Women (Beijing, 1995) and would later become the US ambassador to the Holy See, under the Bush administration.

On the occasion of the webinar, Glendon was the head of the Commission on Inalienable Rights established by the Trump government at the State Department. Three months earlier, in July, the Commission had launched its first report, whose content was analyzed by Kurt Mills, in an article published on openDemocracy in the following terms:

“[The report] …provides an historical (or perhaps an a historical) and theoretical justification for focusing on a reduced set of rights which are compatible with a conservative religious and economic agenda. While many of the so-called ‘new rights’ which are part of that [restrictive] agenda – including LGBT rights – are not explicitly targeted for downgrading to non-unalienable status (and given the prominence of the LGBT rights agenda, it is rather curious that this was not mentioned even once), the message is clear: there are a few core “unalienable” rights which are central to the American ideal – religious liberty, property rights, and rights related to democratic participation”.

In the virtual dialogue, Glendon did not speak about the report that, as suggested by Mills, aims at re-configuring human rights as we know them. But she strongly underlined that, since the adoption of the UN Universal Declaration in 1948, the Church has both appreciated and expressed many reservations about the role and agenda of the United Nations in the realm of human rights work. As an example, she cited a 1989 John Paul II’s observation that the 1948 Declaration lacks the anthropological and moral foundations necessary to sustain the human rights of its title. A bit later, Archbishop Caccia candidly declared that one of his expectations was that the “United Nations can become increasingly Catholic”. Following this rather provocative statement, he paused, smiled, and added: “that is, truly universal“.

When situated in relation to this conversation, the October 2020 speech act on same-sex unions can be decidedly read, as interpreted by Prearo, as a colorful bait to attract attention, while the Vatican intensively played games in the checkboards of high-level policy spheres. One of these games was this rather revealing discussion on the direction of the UN human rights policy agenda, which counted with the contribution of one of the most prominent leaders of what Prearo calls the neo-Catholic movement. These complex dynamics suggest that in 2021 – in addition to key developments in relation to COVID-19 and related crisis – new developments and displacements may unfold in the realm of the Vatican’s gender and sexual geopolitics.

In light of such a horizon, we thought it could be inspiring to offer our readers a sample of the many ambiguous, if not decidedly enigmatic, gestures alluding to homosexuality, LGBTTI rights, same-sex marriage, and related themes that were deployed by Bergoglio, since 2013, when he became Francis I. Check the compilation archived in our library.

Published in December, 2020

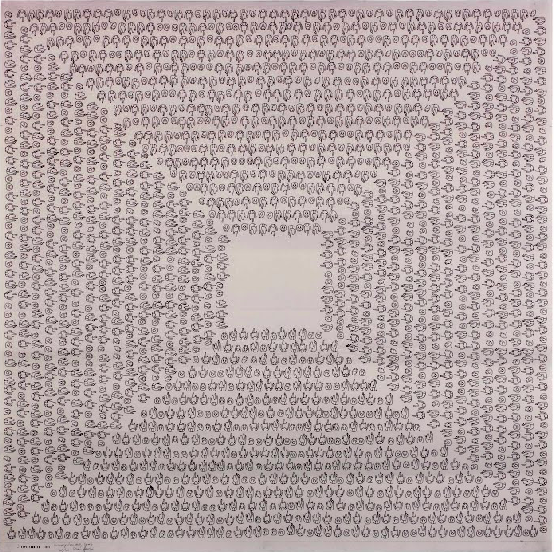

Image: Spectators, by León Ferrari