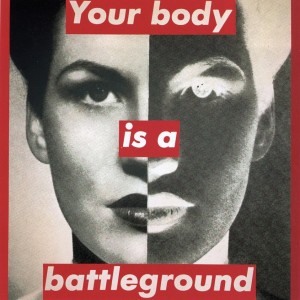

Image: Barbara Kruger

By Sonia Corrêa[1]

As previously reported by SPW (here and here) , for some time now, growing obstacles have been impairing any movement forward in the legalization of abortion in Brazil. Yet, despite many regressions and constraints, feminists groups committed to the right to decide continue to bravely resist anti-abortion forces. This resistance was sharply illustrated at a public hearing held on August 6th, 2015 at the Human Rights Committee of the Federal Senate to discuss a proposition aimed at regulating access to the voluntary termination of pregnancy up to the 12th week. It is in many ways paradoxical that such a progressive proposal would have reached the level of the Senate level when, after the 2014 elections, the overall Brazilian legislative environment is the most conservative it has been since the mid 1960’s. To understand this paradox it is necessary to briefly recap what has happened in Brazil in the realm of abortion politics since last year.

Between August and September 2014, two young women — Elizângela Barbosa and Jandira Magdalena dos Santos — died in Rio de Janeiro after resorting to clandestine unsafe abortions. While public authorities were entirely silent on the matter, these tragic deaths triggered wide indignation in society at large. Dozens of articles were published in both the mainstream press and social media networks; a group of feminists from Rio launched a public petition to legalize abortion that would be presented to federal executive officials and the Supreme Court in March 2015; and, in this same occasion, Congressman Jean Wyllys (PSOL, Rio de Janeiro) tabled a law provision on Sexual and Reproductive Rights in the House, inspired by the Uruguayan laws of 2008 and 2012, which include a chapter on voluntary termination of pregnancy (see Grotz, 2015).[2] During this same wave, a proposal to legalize abortion, technically known as SUG, was also presented to the Senate through Congress’ internet participatory mechanism (e-Legislativo) that allows citizens to submit law reform provisions.[3] Since the provision has gathered more than 20,000 signatures, it has automatically entered the formal legislative process.

On the one hand, these two courageous legal reform proposals are to be praised because they express the plurality of opinion on abortion in Brazilian society and show that resistance is at work in facing a very strong conservative wave. On the other, however, the legislative processing has proven to be daunting. In the House, the provision presented by MP Jean Wyllys was openly at odds with a large number of proposals aimed to further restrict access to abortion, a list that includes a proposal to amend the to included the right to life at conception and the so called Statute of the Unborn. In the Senate, which has been less affected by the recent conservative wave, Senator Magno Malta, an Evangelic pastor (PR – Espírito Santo), has also collected signatures in support of a similar constitutional amendment. Not surprisingly, the Sexual and Reproductive Rights provision is stalled in the House[4], and the route taken by the participatory legislative proposition (SUG) in the Senate is also illustrative of barriers and risks now curtailing any movement forward in regard to the reform of legal abortion.

When the SUG reached the Senate it was given to the Committee on Human Rights, whose president dispatched it to Senator Martha Suplicy (then in the Workers’ Party), a parliamentarian well known for being in favor of legal abortion. But as the 2015 legislative session began, Suplicy announced that she would be leaving the PT and a few weeks later she stepped back from the task of processing the SUG.[5] As would have been predicted, Senator Malta (PR-Espírito Santo) quickly took over the proposal, and strategically processed it as part of a wider strategy towards a constitutional amendment. In order to prevent the Senator from processing the SUG in a way that is biased towards his position, feminist organizations have garnered the support of a few allied senators to make sure the proposition would at least be subject to wider public debates before entering the machinery of the legislative process. The first hearing was held in May, the second took place August 6th, and the next one is scheduled for September 24th.

At the August 6th public hearing, four people represented the anti-abortion camp: Mr. David Kyle, a US citizen who directed the film Bloody Money; the ex-senator Heloísa Helena, who is now a municipal councilor in the state of Alagoas and belongs to the same party as Congressman Jean Wyllys, the PSOL; the Catholic priest Paulo Ricardo; and the political scientist Viviane Pitinelli, who represents the Instituto de Políticas Governamentais do Brasil (a copy-cat of the US based Population Institute). Arguing in favor of women’s right to decide, four feminists also presented their views at the panel: Débora Diniz, an anthropologist and professor at the University of Brasilia/UNB; Márcia Tíburi, a philosopher and professor at the McKenzie University/São Paulo; the psychologist Tatiana Lionço, also a professor at UNB; and myself, Sonia Corrêa, SPW co-chair.

As reported by feminist bloggers who attended the session, the climate was far from smooth. Anti-abortion parliamentarians and activists made up the majority of the audience. The only parliamentarian in favor of legal abortion present was Jean Wyllys, and his interventions were received by the anti-abortion camp with the murmur of laughter and ironic comments. The other MPs who came to the session deployed strong anti-abortion arguments and, quite often, their attitudes and speech were aggressive, if not offensive.

For example, Jarid Arraes, in an article published in Revista Forum, describes how the panel was interrupted as soon as it started because MP Leonardo Quintão (PMDB, Minas Gerais) wanted to protest against the name of the McKenzie University appearing in Márcia Tíburi’s identification card. His reasoning was that the Presbyterian Church, which maintains the institution, is not in favor of abortion. Márcia argued that she was not speaking on behalf of the University, but she also could not entirely detach herself from her professional position. The response did not appease MP Quintão, who, after making several cell phone calls, received a public statement signed by the dean of the McKenzie University explicitly stating the institution’s position on abortion (accepting it only when a woman’s life is at risk), which was read aloud by Senator João Cabiberibe, who presided over the session. In the same high pitch tone, MP Flavinho (PSB, São Paulo) called those who advocate for abortion rights ‘shameless people’ and said, in a gossip-like fashion, that he found it very strange to see members of the LGBT movement calling for abortion rights. Arraes also noted how, on various occasions, the mere articulation of the terms “feminism” or “gender” was enough to trigger booing.

Structured as an open confrontation between the camps in favor of and against abortion, the public hearings held by the Senate’s Human Rights Commissions do not exactly enable dialog and in-depth democratic deliberations on the subject. It should be noted that the prevailing disrespectful atmosphere is not peculiar to this debate. Broadly speaking, it feeds into and reflects the climate of intolerance and disqualification of political adversaries now palpable in Brazilian politics [see Bernardo Carvalho in Folha de São Paulo, in Portuguese].

Despite these limitations, the hearings constitute a privileged stage to chart the arc of reasoning that Brazilian feminists are developing in defense of women’s reproductive autonomy, as well as the arguments currently being propelled by anti-legal abortion forces.

What the voices against legal abortion have said:

Mr. David Kyle who was the first to speak at the session, showed a section of the film he directed, which tell the stories of women who have died in legal abortion clinics in the US. His aim was to provide the audience with solid evidence that “safe abortions do not exist”. He then referred to a whole set of supposedly scientific ‘biomedical data’ on the collateral effects of abortion on women’s health. In addition to these biomedical arguments, Mr. Kyle’s tone was also explicitly political. For example, he claimed that “the current US political regime is a tyranny ruled by the undemocratic decisions of the Supreme Court” and that Brazilians now have a privileged opportunity to democratically vote against abortion. He also indicated that those advocating for the right of the fetus should be recognized as the only authentic human rights movement in the world today.

The ideas presented by Ms. Viviane Pitinelli, in contrast, were not so ideologically loaded. She provided a patchwork of ‘academic analyses’ aimed at demonstrating that if abortion is legalized, high abortion rates will lead to further fertility decline, population aging, and inexorable negative effects on the Brazilian labor market and social security system. Though couched in technocratic terms –and directly quoting from theses developed in recent years by some Brazilian demographers —[6] the argumentation had flaws. Through emphasizing the future effects of fertility decline, Ms. Petinelli correlated these effects with the “demographic bonus”, a model conceived to address past and present trends in fertility and age structure. Not only did she insist on the current absence of good public policies that prevent unwanted pregnancies, she also never mentioned that the prevalence of contraception use in Brazil is very high, or even that this prevalence is, in fact, what explains the rapid fertility decline that has occurred in the last 30 years.

The Catholic priest Paulo Ricardo, who followed, returned to a high-pitched line of ideological argumentation. The priest, who is known for his radical anti-feminist positions[7], began by affirming that Brazilian feminists are mere puppets in the hands of an international conspiracy comprised by private foundations, social scientists, and North American-feminists.[8] In his view, since the 1970s these forces have been engaged in a global endeavor of social engineering geared towards reducing population rates, normalizing abortion, and dominating the Third World. This ‘master conspiracy theory’ mimicking anti-imperialistic discourses is directly borrowed from materials produced by very well funded, US-based anti-abortion organizations. Furthermore, as sharply noted by the feminist blogger Lola Aranowitz,[9] it is a blunt adaptation of anti-Semitic ideologies of the early 20th century – attributing all evils of the world to the doings of a Jewish manipulative global elite – into the realm of feminism and abortion rights struggles. Father Ricardo did not end there, however. He contested the estimated figures of the number of clandestine abortions in Brazil (around 1 million per year), saying that this figure would never be higher than 100,000 and finalized his argument with the daring affirmation that secularity (or laicité), always claimed by feminists in debates around legalizing abortion, is nothing more than a “dirty trick”.[10]

After this diatribe, the ideas raised by ex-senator Heloísa Helena initially sounded quite balanced. She was the only anti-abortion voice in the room to say that, though against a law reform allowing for abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, she does not support further restrictions in the present legislation. She has also criticized both religious and secular fanaticism because “they have proven to be historically deplorable”. In a subsequent step, she furthered the debate initiated by Father Ricardo regarding the abortion figures but through a different and more consistent angle. Presenting figures collected from the public health system database, she correctly alleged that abortion related maternal deaths are not so numerous (around 140 per year) and that, in light of those figures, “legalizing abortion does not prevent a major public health problem”. Even though the data she presented is correct, what was rather striking was that she insisted on this argument even after recognizing that even a single death caused by clandestine abortion would be highly regrettable. Then, at the end of her talk – further distancing herself from the quite reasonable lines of argumentation she had been developing – she waved a tiny plastic fetus at the audience while frantically defending the right to life at conception in order to preserve the biological miracle of life and the unique genetic pool of each individual.

What feminist voices have said:

In my argument I developed a series of complementary ideas connecting women’s right to decide to the need to decriminalize/legalize abortion, as well as to democracy. My first observation was that consistent, deliberative debates on abortion rights can deepen and consolidate Brazilian democracy, which remains frail and still prone to authoritarian temptations. To recap the long history of laws criminalizing abortion and its connection to women’s political and civil rights, I quoted Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg from the US Supreme Court when she remarked that reproductive autonomy is a requisite for women’s full participation in public life.

I then argued that the criminalization of abortion must also be critically examined through the same lenses that have identified the contradictory coexistence in most of Latin America between consolidated democracies and the high levels of incarceration rates that result from hypercriminalization (specifically, but not exclusively, related to the so called ‘war on drugs’). In Brazil, for example, the current prison population is the fourth largest in the world and the enforcement of criminal laws is highly selective, if not deeply racially and socioeconomically biased. Finally, I briefly shared a set of judicial interpretations developed by Brazilian legal experts[11], which challenge the constitutionality of the 1940 Penal Code articles that even today criminalize the voluntary termination of unwanted pregnancies.

Debora Diniz, in her turn, analyzed the conditions presiding over unsafe abortion in Brazil from an entirely different angle. Using the findings from substantive empirical research on the subject, which she has been engaged in for many years – in particular a recent study involving teenagers and prostitutes in the capital town of Piauí – she portrayed, in strong colors, the reality of the worlds in which Brazilian women resort to clandestine abortion. She began by recounting that around 7 million women, aged between 18 and 39, have illegally terminated unwanted pregnancies and that the large majority of them have used smuggled Misoprostol. Clandestine abortion clinics still exist but no consistent research exists about their practices.

Diniz then called attention to the bias of existing criminal laws that restrict women’s reproductive autonomy to those situations in which they are victims of rape or grave health conditions. In opposition of those against legal abortion, she reiterated that abortion is a major health problem: not just because it remains one important cause of women’s death, but also because 50% of women who abort resort to utilizing public health care. These women, she underlined, are often denounced as criminals and ill-treated. Additionally, and of equal importance, the number of services abortion under the circumstances of rape and anencephaly has shrunk in recent years.

Her central argument was that women who abort are ordinary women; women who are our relatives, friends, neighbors, or belong to our religious communities. Large numbers of them are married, have children, and are engaged in the labor market. But in order to deflect the blunt reality of abortion as a health need of ordinary women, a spectacle has been created by anti-abortion forces in which these women are portrayed as irresponsible or immersed in sexual hubris, and where abortion is predominantly imagined to be exclusively practiced by teenagers or prostitutes. In sharp contrast, the embryo is represented as an innocent newborn. Ordinary women who have abortions emerge from this ideological operation “as reckless creatures who have committed infanticide” and their experience and rights are “erased in the name of a patriarchal order that makes use of the most powerful state instrument: criminal law”. Diniz has also correctly remarked that if laws criminalizing abortion were consistently implemented, the Brazilian levels of incarceration would geometrically explode.

The point of departure from Tatiana Lionço, who came next, was to note that currently in Brazil, women who dare to speak on matters viewed as morally condemnable, such as abortion, are quite often easily prone to political and personal attacks and disqualification (she also remarked that she herself had a few times been the target of these vicious intimidations).[12] Consistent with this criticism, she then emphasized the critical importance of all forms of democratic participation in regard to legislative debates on the legalization of abortion, and praised the SUG proposition as one bold illustration of the way open participatory mechanisms can positively set new agendas at high parliamentarian levels.

Along the same line of reasoning, she underscored that, in democratic conditions, majoritarian positions cannot silence the views and voices of minorities. In her view, even though many Brazilian women may not be in favor of legal abortion, this is not a good enough reason to preclude the subject from debate and much less to justify the censorship or disqualification of those who admit to having resorted to clandestine abortions or of those who call for its legalization.

Then, as a member of the Regional Council of Psychology (CRP), Tatiana shared the formal position defined by the Federal Council of this professional association (CFP) in regard to abortion related matters. In 2010, its VII National Congress approved the legalization of abortion. Two years later, in 2012, when a reform of the Penal Code was being discussed in the Senate, a proposal was made to make abortion legal up to the 1212 week of pregnancy. Within it a requisite was included in the draft text that women requesting the procedure should be previously screened by a professional team, which included a psychologist. At this occasion the CFP deliberated on the matter and issued a formal position that fully supported women’s autonomy of decision and rejected delegating the power of this decision to any type of professional. Of no less importance is conscious objection, which the CFP recognizes as a non-negotiable professional right, while also ruling that this right cannot impede access to any type of medical procedure, as access to services must be ensured by institutional systems.

The last feminist speaker was Márcia Tíburi. She explored the ‘question of abortion’ as a bio-political matter that, in her view, is inscribed in the “cynical circle of sexist social formations”. One key feature of this circle is a “pact of pretense” within which women make it sound as if they have not had an abortion when others speak against it. Consequently, the women who publicly declare to have had an abortion or those who openly struggle for legalization break through this circle of cynicism and are depicted as immoral. Tíburi also examined the way dominant positions on abortion are organized around a series of fallacies. The first of these fallacies is that the debate is always framed in terms of the abortion problem, when in fact what is at stake is the legalization of the procedure. The second fallacy is that whenever the topic is discussed as a problem, religious and scientific “authorities” — engaged in the surveillance of social practices — are called to speak, thereby silencing or disqualifying women’s voices. She also cited the fallacy of maternity and maternal love that erases women’s desires and depicts women who have had abortions as unnatural because they refused the “irresistible natural drive of maternity”.

The other fallacies that must be critically looked at in Tiburi’s analysis are those specifically concerning the life of the embryo and the frantic defense of life per se. In the first case, she noted that one main fallacy is the supposed superiority of the embryo, which subordinates women’s bodies to compulsory pregnancies. The other is the fundamentalist conviction that the acceptance of this superiority, through maternity, is the only path through which women are spiritualized. In the second case, the most glaring effect of the frantic appeals to the value of life is that the social, ethical, and political complexities of lives as they are lived are entirely sidelined and framed in highly abstract or narrow biological terms. In her final argument at the end of the session, Tíburi — who had begun her argument calling for the discussion to be subject to a generous reflection without moral judgments — was deeply disappointed by the atmosphere of intimidation that prevailed in the session and the parliamentarians’ lack of preparation to reasonably address the subject under discussion, which prevented a more balanced deliberation from happening.

In conclusion

Underlying the virulence and aggressiveness, which marked the climate of the second public called by the Senate Committee to debate the SUS on legalizing abortion, blatant androcentric attitudes and patriarchal tutelary tenets that were more than palpable. Regardless of this climate, feminist voices were not intimidated and were able to articulate complementary lines of reasoning in defense of women’s reproductive autonomy. On the other side, the voices contrary to legal abortion resorted to attacks and accusations while also throwing in many emotional appeals, not exclusively regarding the life and suffering of the fetus, but also in regard to the detrimental effects of women’s health and life.

More significant, however, is the vast array of ‘secular’ lines of argumentation against abortion by those who defend its legalization – demographic and economic analysis, epidemiological data, and even supposedly anti-imperialist stances — that circulated during the session. These discourses are decidedly distant from the discourses around sin, guilt, and remorse — or even more conventional moral arguments – that to which anti-legal abortion forces predominantly resorted to a few years back. This reframing is here to stay and, as noted by a wide variety of authors, is flagrant evidence that today’s dogmatic religious forces no longer engage with abortion as a doctrinal matter, but as a bio-political issue tout court.

[1] I thank Fábio Grotz, SPW communication assistant for collecting information for this article and, most principally, my panelist colleagues and the feminist bloggers Jarid Arraes, Lola Aranowitz and Paula Guimarães because without their writing for and articles on the public hearing it would have been impossible to write these few pages. I am also grateful to Ana Ramirez, Kelly Gavigan and and Jacob Milner who generously reviewed the article.

[2] The PSOL – Partido do Socialismo e LIiberdade– is a dissidence from the PT. It took form in 2006 after the first round of corruption scandals, known as the Mensalão, stained the ethical standards of the PT administration. Jean Wyllys was elected in 2010 and is the only openly gay Brazilian Federal MP. Since his first mandate he has taken on board all of the harsh sexual and reproductive rights causes, such as the defense of same sex marriage, decriminalization of sex work, provisions regarding HIV/AIDS, debates on obstetric violence and abortion reform.

[3] The proposition was created and mobilized by a young cyber activist previously involved in campaigns for the decriminalization of marijuana.

[4] After having been processed by the Committee on Social Security and the Family, the provision was appended by its rapporteur into the package of regressive legislation on the matter, making it very difficult for it to prosper.

[5] When she was a member of the House in the 1990’s, Senator Martha Suplicy in fact tabled one of the various provisions aimed at legalizing abortion. But her recent political shift (she has requested her affiliation to the PDMB) suggests that she can no longer be counted as a supporter of women’s rights issues. In fact, as this article was being finalized the Brazilian press announced that she has personally invited MP Eduardo Cunha, the Evangelical president of the House to the act of affiliation to PBMD.

[6] As it is the case of demographer Ana Amélia Camarano who has published a series of articles on the negative effects of aging and fertility decline.

[7] The priest is a follower of the extreme right Brazilian polemist Olavo de Carvalho and has often declared that feminism is the worst evil presently affecting women’s lives.

[8] He directly named the Rockfeller, Mac Arthur and Ford foundations, as well as the social scientist Kingsley Davis, the feminists Adrianne Germaine and Francis Kissling, the later quoted as a feminist voice who has criticized the US foundations.

[9] http://escrevalolaescreva.blogspot.com.br/2015/08/a-ignorancia-dos-homens-ao-tutelar-o.html

[10] Regrettably, Senator Capiberibe, who was presiding over the session, was not able to comment on whether this terminology is appropriate to qualify as one of the tenets of the Brazilian republic.

[11] In the session I have specifically cited the writings of judge Jose Luiz Torres

[12] Not long ago, Lionço was personally and viciously attacked by religious and right-wing parliamentarians. MPs Jair Bolsonaro and Ronaldo Fonseca accused her of being a promoter of pedophilia because of her public positions on education and sexual diversity.