By Sonia Corrêa & Rajnia de Vito

Recently, references to pedophilia have increased vertiginously in Brazilian social networks and the press. At first glance, this phenomenon might be attributed to the unwarranted accusations against YouTuber Felipe Neto, who bluntly publicized his opposition to Bolsonaro. Not only did he publicize it, but he managed to be featured in an op-ed video in The New York Times with the title “Trump Isn’t the Worst Pandemic President”. The hashtags #AllAgainstFelipeNeto and #FamiliesAgainstFelipeNeto echoed fake news and became a trending topic on Twitter on July 27th.

Felipe Neto, however, was not the only target of this accusatory campaign. A few days earlier on July 22nd, pedophilia accusations against Supreme Court justices also circulated on social media after former congressman Roberto Jefferson – Jefferson is a new staunch ally of Bolsonaro since he has become closer to “traditional” parties – accused the Supreme Court of attacking the Minister of Women, Family and Human Rights, Damares Alves, for standing up to pedophilia. Before that, on June 10th, a Twitter account published a conversation implicating YouTuber PC Siqueira (a friend of Felipe Neto) in child pornography crimes. Also, Felipe Neto’s brother, Luccas Neto, who is also a YouTuber, was the target of a defamatory campaign accusing him of “incitement to pedophilia”.

This is not the first time in Brazil that there has been a wave of accusations of and moral panic about pedophilia. It happened, for example, from 2007 to 2009 when a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) regarding pedophilia was convened in the Senate, presided over by Magno Malta (PR-ES), to whom Damares Alves, current Minister of Women, Family and Human Rights (MMFDH), was an advisor for over ten years. This CPI was proposed following the launch of the National LGBTT Health Policy at the First National LGBT Conference, which had great international visibility (and in which the then-President Lula participated) and took place concurrently with heated debates on a proposition to criminalize homophobia.

That moment of intense discussions around pedophilia and the rights of LGBT people preceded the attack by neoconservative religious parliamentarians against a series of educational videos launched by the Ministry of Education in 2011 to promote respect for sexual diversity, which would lead to its suspension by then-President Dilma Rousseff. This material, known as the “gay kit”, would continue to reverberate politically. In the 2018 general elections, the topic once again erupted into the public debate when it was used by the Bolsonaro (PSL) campaign to attack candidate Fernando Haddad (PT) for having distributed “dick baby bottles” (baby bottles with a penis-shaped nipple) in the public education system to “teach boys how to be homosexuals”.

In 2020, the new wave “against pedophilia” began long before the accusations made in July against Felipe Neto, ministers of the Court, and others. At the end of April, in what seemed to be the biggest crisis of the Bolsonaro Administration caused by the exit of Minister of Justice, Sergio Moro, the president appointed André Mendonça, who had been the attorney general of Brazil since 2019, as the new minister. Mendonça is a lawyer and a Presbyterian pastor. As researchers Brenza Carranza and Christina Vital commented, the appointment signals a closer relationship with the evangelical base in Congress and society and signals the eventual appointment of André Mendonça as Supreme Court judge.

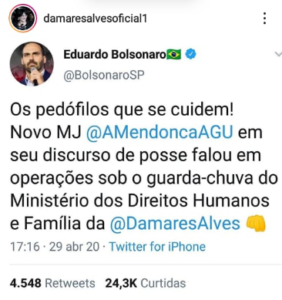

This nomination was widely celebrated by members of the government, especially Damares Alves, but also by Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro (PSL), who affirmed Mendonça’s firm commitment to the fight against pedophilia.

Following this, a study by Bites data analysis agency found that since May, Minister Alves has increased the usage of the term pedophilia on her social networks, exceeding the number of mentions made last year. Between late July and early August, she posted 18 messages on the topic, including a video warning about the dangers of the Internet for children and adolescents and more specifically child pornography.

Pedro Bruzzi, from Arquimedes Consulting, repeated the thesis, in our view mistaken, that pedophilia, like other themes of the so-called moral agenda, was again being used as a “smoke screen” to blur the effects of the political crisis that began with the departure of Moro and worsened in the critical moment of the pandemic. Our disagreement lies in the fact that, in our point of view, gender and sexuality issues are at the heart of the shift to the right, even when they can also act as a distraction. Rubens Valente states that the current prioritization of pedophilia as a government campaign also has the function of projecting the impression that the government not only identifies problems but also offers solutions.

Finally, anthropologist Isabela Kalil noted that the new focus on pedophilia is linked to the creation of the Family Observatory, announced by the MMFDH in April. According to this anthropologist, this agenda has been organized for some time in concert with the program for sexual abstinence (launched in December 2019), and is now more openly focused on the appreciation of the family and the “protection of children”. This agenda to combat pedophilia is both a public policy at the core of the government’s agenda and a scapegoat that, depending on the circumstances, can easily be transmuted into an accusatory category against people who criticize or try to contain its will. This new wave can be read as a new manifestation of the crusade against the metamorphic “gender ideology” that, as already mentioned, was one of the contested issues in the 2018 election.

Transnational connections and national particularities

This largely unique trajectory, however, does not fully explain what has been seen in Brazil since April. The recent anti-pedophilia eruption has easily traceable connections to ongoing dynamics in continental and global cyberspace. In early June, the evangelical digital vehicle Noticia Cristiana replicated a U.S. story that claimed there was pressure to include “pedosexuals” in the list of groups claiming the rights of the LGBTTI population. The article published the image of the flag of a supposed group called MAP in pink and blue, partially mimicking the trans movement’s flag. In English, MAP is the acronym for “minor-attracted person”, a medical-psychiatric category that has never been used politically.

The flag with the acronym was posted next to a photo of a LGBTTI demonstration organized by the organization Sentiido, which fights for the rights of the LGBTTI population in Chile. This post seems to have triggered a viral reaction on the digital networks of Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, and Colombia, and also in Bolivia and Mexico, although with particularities. In Google Trends records, the search for the terms “pedophilia” and “pedophile flag” increased dramatically, reaching peaks in June and July. This post and the way it went viral may have been mobilized to create confusion in relation to May 17th, the date that marks the International Day Against LGBTophobia and when civil society organizations, networks, and individuals flood the web with stories of activism and celebrations of sexual diversity.

However, the wave also has traces of being “reheated” news. According to the U.S. fact-checking agency Snopes, the same news surfaced on Tumblr in the U.S. in June 2018 after it circulated for the first time in 2017. It would then be published in July 2018 by pro-Bolsonaro Brazilian media outlets Terça Livre, Expresso Diário, and Portal Livre at the moment immediately prior to the election process that resulted in the election of Bolsonaro and in which the topic of pedophilia would produce a circus of horrors.

This reiteration is not accidental; it is a method: reactivating this kind of news works like laying bait on social networks to capture attention, causing the content to eventually become a trending topic. In the countries in the region where this “bait” went viral in 2020, anonymous Twitter accounts also published the photo of a supposed new LGBT flag with the caption “What is pedosexuality? – an extremely necessary thread”; supposedly differentiating pedosexuality from pedophilia, pedosexuality would be a new category of sexual orientation to describe not only the desire for minors but also the consent of the child or adolescent desired.

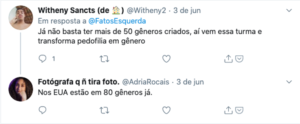

In Brazil, “pedosexuality” became a trending topic on Twitter on June 3rd, although the original post was quickly deleted. The profile that posted the note admitted to its followers, all also anonymous, that this had been a successful “bait” and was congratulated for its exceptional achievement. One of these congratulations juxtaposed a Soviet Union emoticon and an LGBT flag emoticon, thus reactivating the link between “gender ideology” and Marxism but now through a frame that links the “LGBTTI ideology” and communism — a key link that has been exploited in Poland since last year.

This link is neither new nor exceptional. Most of the threads we examined on MAP made the classic association between communism, the left, and pedophilia. However, in a retweet, a user included the petitions that demanded justice for George Floyd and for little Miguel (the son of a housekeeper who was only 5 years old and died due to his mother’s employer negligence, falling from the ninth floor of a luxury condo in Recife). This retweet enlarged the association of pedophilia with the antiracist struggle. Another user, supposedly a feminist because of the famous working woman profile picture, claimed “Death to Bolsominions” while also defending “pedosexuality”. In all cases, there was a chain of floating signifiers used by the right for some time, which allows them to “glue” together cultural Marxism, the Frankfurt School, protection of minorities, feminism, “proliferation of genders”, and pedophilia.

However, in Brazil, a new trope would later be included in this chain when attacks on Felipe Neto broke out promoting a new category: “age fluid”. As the newspaper O Globo analyzed, this term would supposedly define the category used by people who have a “generational identity” that varies from the actual age, which can be associated with different gender identity than the one assigned at birth, that would justify their sexual desires for children. As also investigated by Snopes, this is not a Brazilian invention, but another piece of advertising imported from American social networks. In Brazil, it was associated with the “denunciation” according to which Felipe Neto would promote the legitimization of this concept with the connivance of the Supreme Court. These deliberate and very heterogeneous confusions can be read as a metamorphic ramification of arguments developed, since the 1990s, against feminism and homosexuality and grouped under the term “gender ideology” invented by ultraconservative Catholicism, that is, the Vatican and its allies (read more on the genealogy of the term here).

Another actor in the “fight against pedophilia”: QAnon

In the aftermath, the attacks would resurface with great force with the digital proliferation of the American QAnon movement. The acronym refers to Q, an anonymous profile, first on the 4Chan network and which today operates on several networks, that belong to a supposed U.S. government official dedicated to the propagation of conspiracy theories. In the U.S., the profile gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a result of denouncing a supposed mobilization of Democrats to install satanism and pedophilia, calling for a vote for Trump as the only possible opponent of this strategy.

Under a hashtag calling for “child protection”, #SaveTheChildren, QAnon activists denounce not only major figures from the Democratic party, but also millionaires and Hollywood celebrities allegedly involved in this “pedophile-satanist” scheme, and also repudiate health measures against COVID-19, evidence regarding the climate crisis, conventional media’s journalistic production, and scientific evidence.

Nor is QAnon exactly a novelty, as an enlightening article in the Spanish newspaper El Diario argues, examining the movement’s main references. Its origin can be traced to the 20th century, to the fabricated Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion, a document that described a secret network of powerful Jews who controlled the world and that was used to justify anti-Semitism. Currently, its closest analogue is the Pizzagate episode, which involved the dissemination of a conspiracy theory in 2016 that implicated Hillary Clinton, then a U.S. presidential candidate, in a child trafficking network, and which ultimately led someone influenced by this theory to open fire on a restaurant where trafficked children supposedly were.

At the end of June, QAnon wave reached Latin America, especially Argentina and Costa Rica, although, as reported by BBC, social media accounts and groups dedicated to the theme emerged in Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay as well. In Brazil, the movement would in fact become prominent on August 27, when the book “The QAnon Movement – Introduction to the History that Will Change the World” was launched with the financial help of crowdfunding. As Odilon Caldeira Neto, of the Extreme Right Watch, argues, pedophilia is at the heart of the conspiracy theories propagated by the movement because it very easily incites moral panic beyond ultraconservative sectors and is an effective instrument to discredit political enemies, as seen in the case of Felipe Neto.

Conclusion

As we have seen, waves of accusations and moral panic associated with pedophilia have a long history. In the other countries of the region, what we have seen since May 2020 may be just a new wave. However, in the U.S. and Brazil, this spiral will not cool down in the short term. In the U.S., the accusation of pedophilia is already inscribed in the plot of a fierce electoral dynamic. In Brazil, as we have seen, “fighting pedophilia” is now a priority of the Bolsonaro government; that is, the state apparatus is a permanent source of discourses on the subject. In addition, there is nothing to indicate that Bolsonarism virulent reaction to its critics will wear off and, therefore, the strategy to use pedophilia as a category of disqualification of enemies will continue and the term will continue to hover in the digital world.

It is, therefore, about being prepared for new spirals, tracking their origins and, above all, not replicating posts, threads, or images, not even as a denunciation, because this only gives more grist to the mill of those who propagate these ideas. It is also crucial to juxtapose the malignant specter propagated by right-wing networks and religious neoconservatism with the plasticity of gender and sexuality and the quantitative data on the tenebrous reality of sexual abuse, as Andrea Domingues does in the excellent article “Monster Under the Bed”.

In the case of Colombia, which she analyses, in 2018, 23 thousand girls, boys, and adolescents were sexually abused, 10,258 of whom were girls between the ages of 10 and 14. In addition, 77 percent of these abuses happened at home, and 77 percent of the perpetrators were people close to the victims, 14 percent of whom were their fathers and 2.3 percent their mothers. As is the case in Brazil, which gained great visibility with the girl from Guriri case (abused by her uncle for 4 years) it is worth recalling Domingues’s recommendation:

Therefore, if we keep chasing pedophiles wrapped in pink flags, who are portrayed in social media as angry activists marching around advocating for their rights, we will lose sight of the elephant in the middle of the room, the monster under the bed.