In the March issue of SPW’s Sexuality & Art, we feature the works of American black artist Mickalene Thomas. She invites us to decolonizing look into traditional paintings by pooting the black female bodys and their subjectivities literally at the center of her work.

In 1955, Emmett Till, a black child, was pistol-whipped, beaten, and eventually shot and killed in Mississippi for allegedly flirting with a white woman. In the fifty-eight years since Till’s infamous murder, the American civil rights movement has made great progress for the nation’s race relations, but the ideology that led to his death is still active. On Memorial Day, 2013, Tremaine McMillian, another black child, was tackled to the ground and put in a chokehold by Miami-Dade police officers because they claim he gave them “dehumanizing stares.”1 For these boys and millions of other African Americans, the threat of assault, murder, or rape is the consequence for looking at or speaking to white Americans.

In her essay “Representations of Whiteness in the White Imagination,” bell hooks argues that the control whites exert over the black gaze is integral to white supremacist oppression. African Americans, during and after the institution of slavery in the United States, were expected to be both invisible and unseeing. “Black folks were compelled to assume the mantle of invisibility, to erase all trace of their subjectivity…so that they could be better, less threatening servants,” she claims.2 By exacting physical and psychological violence against any black individuals who expressed their subjectivity, whites could live in a world in which they imagined blacks weren’t looking at or judging them. The ideological control of the black gaze is seen in the cases of Till and McMillian, where the mere display of subjectivity was dealt with swiftly and violently.

This historical and social context lends the work of New York–based painter Mickalene Thomas a radical and subversive dimension. Thomas’s Origin of the Universe 1 (2012), an acrylic, oil, and rhinestone appropriation of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World, 1866), is a forceful assertion of Thomas’s gaze, which is always and forever black. The Origin of the World—which sits in the Musée d’Orsay, a revered temple to white subjectivity—propagates an ideology that places whiteness at the center of human experience.

L’Origine du monde puts on display a woman’s naked torso and pelvic region, with the woman’s genitals dominating the painting. The work and its title connect female reproductivity to the provenance of civilization and humanity—not altogether a gross exaggeration. But in Courbet’s painting, the origin of the world is, of course, a white woman. She is not a Middle Easterner, as the Christian tradition would have it, or a black African, as anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and human geography suggest.

Thomas retells this story. Origin of the Universe 1 depicts a black body in the place of Courbet’s Irish model, Joanna Hiffernan. In Thomas’s rendition, the subject’s pubic hair and nipples are created with rhinestones. The use of the non-traditional material of rhinestones, a signature element in her work, nevertheless emulates techniques in the European canon. Thomas says that her use of rhinestones exists somewhere between Georges Seurat’s pointillism and Aboriginal dot painting.3 Without appearing comical or frivolous in Origin of the Universe 1, this technique takes away some of the seriousness of Courbet’s painting. Thomas grounds her alterations in art history while simultaneously offering an alternate to it.

What is more, rather than hiring a model, Thomas herself posed for the painting. By using her own body, Thomas sheds some light on her use of the word “universe” rather than “world” in the work’s title. While it could appear to be one-upmanship over Courbet, this shift suggests a personal universe and sense of subjectivity, rather than a bombastic cosmological claim. Thomas has said that in this work, as well as other similar works in the Brooklyn Museum’s 2012 exhibition Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe, she wanted to “expand the idea of my universe.”4 The work doesn’t seem overly concerned with pointing out that the origin of the human world was ancient East Africa and its inhabitants. Instead, Thomas affirms her own subjectivity, its centrality to her world, and its ability to see and analyze whiteness.

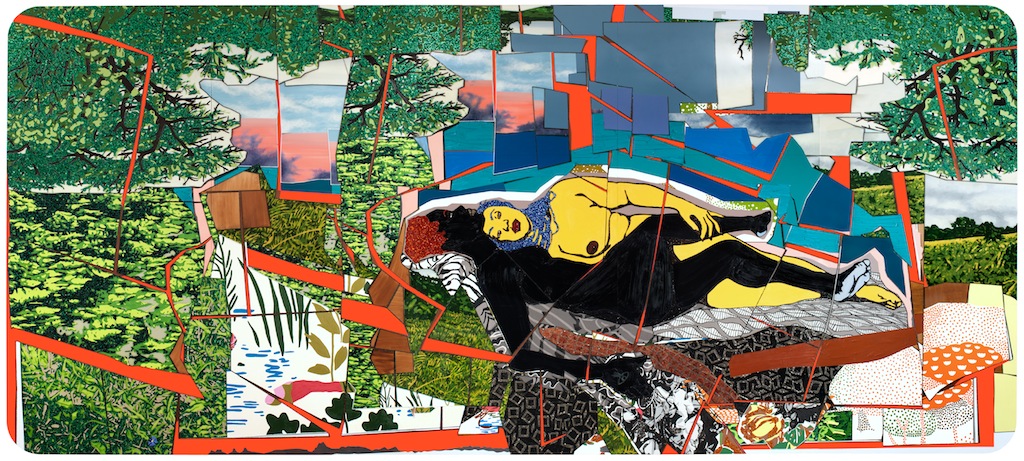

Thomas’s wood panel painting Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires (2012) applies the same treatment to Courbet’s Le Sommeil (1866), an erotic painting of two nude white women entwined in one another’s legs. Like Origin of the Universe, Sleep diverges from the more realist style of Courbet’s original. One woman’s skin is nearly pitch black and the other is the color of a lemon, her race only known because of the work’s title. Like the use of rhinestones, which are also present in Sleep, the cartoonish style destabilizes the grand and austere quality of Courbet’s work. Thomas replaces the god-like eye of Courbet with a personalized view of the world, one in which she can see both similarities and differences among women of different races and times. By trying to nullify the black gaze, the ideology of white supremacy attempts to create an apartheid of subjectivity, where two mutually exclusive ways of being and seeing exist side by side but can only interact superficially (or subversively). By depicting black women in a scene of white desire, Thomas erodes the false boundary between an illusionary white world and a black universe, demonstrating that one can see both similarity and difference in the individuals who supposedly inhabit these worlds.5

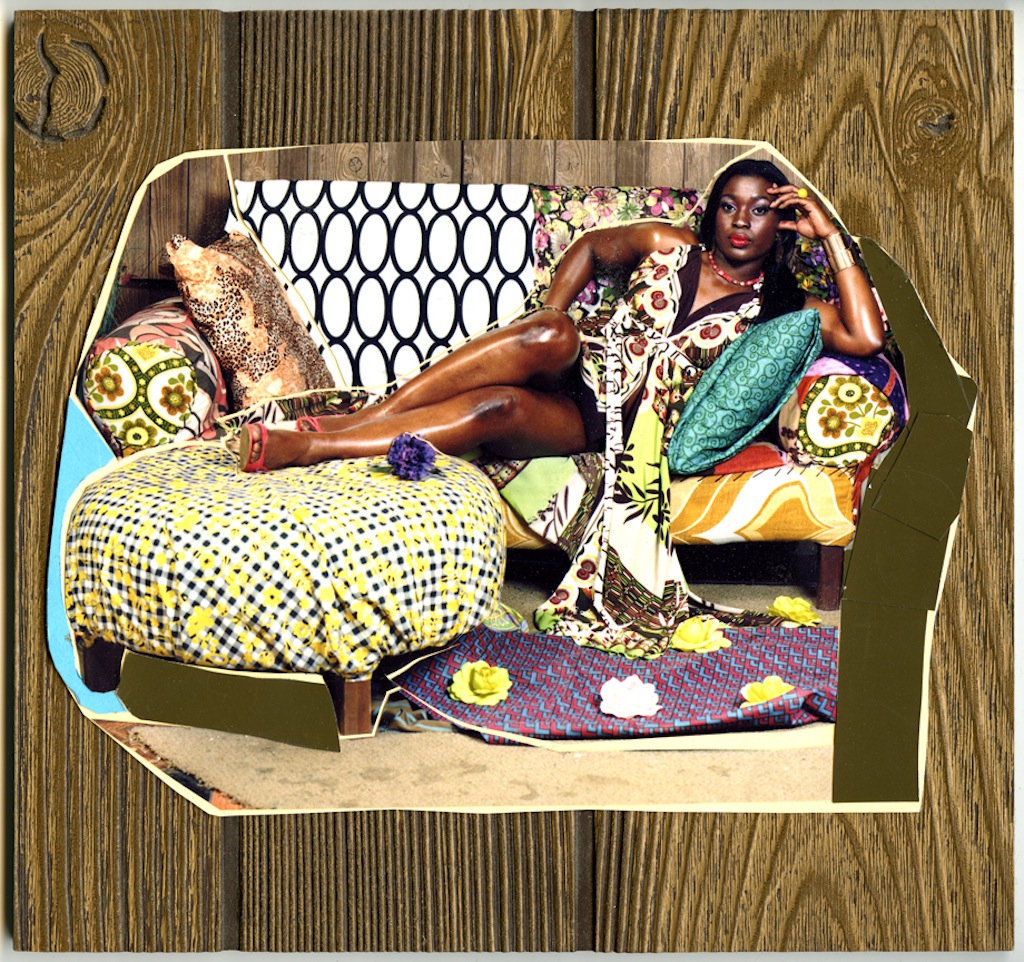

Thomas says her work “is about presenting beauty and the black body.” She proclaims, “You’ll see me, therefore I exist.”6 But her work attempts this in a manner more elaborate than painting beautiful images of black individuals. In many of her works, she inserts herself or her models into scenes that were previously the domain of white women—that is, white women as seen by white men. Her agency and ability to see and be seen, analyze, judge, and synthesize are undeniable, and she places the black gaze front and center in all of these works. “To see yourself and for others to see you,” she explains, “is a form of validation.”7 In “Representations of Whiteness,” hooks concludes with the argument that by critically examining white control of the black gaze, “We both name racism’s impact and help break its hold. We decolonize our minds and our imaginations.”8 Though Thomas, as a respected and known artist, is afforded a grand luxury that McMillian and millions of others are not, it’s clear from her work that political acts in galleries and museums have real power.

Notes

- Zack Beauchamp, “Police Allegedly Assault Black Kid Carrying A Puppy For Looking At Them Wrong,” Think Progress, May 31, 2013,

- bell hooks, “Representations of Whiteness in the Black Imagination,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press, 1992), 168.

- “In the Studio with Mickalene Thomas,” Artsy, accessed September 8, 2013.

- “Mickalene Thomas Studio Visit,” video clip, accessed September 8, 2013, YouTube.

- Female homosexuality is often eroticized and desired as in Le Sommeil, as well as in much pornography. But this semblance of acceptance is highly restricted: such scenes must often be private, sexually explicit, controlled by men, and the subjects must adhere to popular beauty standards. When some or all of these conditions aren’t meant, violence or the threat of violence is often present. For example, two women holding hands in public can sometimes be more controversial than a hardcore lesbian sex scene produced by a male pornographer featuring young, thin, blonde women.

- “Mickalene Thomas Studio Visit.”

- Ibid.

- hooks, 178.

Images

- Mickalene Thomas. You’re Gonna Give Me The Love I Need, 2010; rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel; 96 x 144 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

- Mickalene Thomas. I Learned The Hard Way, 2010; rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel; 120 x 96 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

- Mickalene Thomas. Origin of the Universe 1, 2012; rhinestones, acrylic, and oil on wood panel; 48 x 60 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

- Mickalene Thomas. Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires, 2012; rhinestones, acrylic, oil, and enamel on wood panel; 108 x 240 in. Courtesy of the Artist.