In November 2015, on the trail of the “feminist occupations”, we published for the first time the work of the black painter Rosana Paulino, whose central themes of interest are the feminine body, blackness and racism, and the ancestral memory and marks of slavery.

We came to publish her again at the occasion of the 130th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in 2018, and, at the end of this year, we retake Paulino’s work, which evokes to us the social and historical places occupied by black people in Brazil, and by black women in particular. In light of the global political landscape which promises worsening conditions to all of us, the markers of social difference of race/colour and gender as displayed by Paulino reminds us of ideas of social justice and intersectionality.

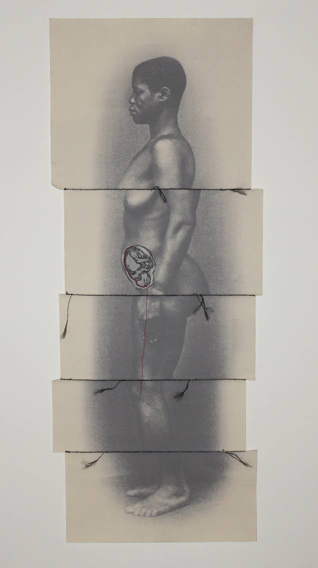

Indeed, Rosana makes us face the place of extreme vulnerability and precarity that black women experience when trying to exert their bodily autonomy, as illustrated by the case of the Brazilian woman Ingriane Barbosa, killed by a castor’s stalk used to perform her abortion, which marked the year of 2018. According to data from the Ministry of Health, revealed in the public audience for the ADPF 442 at the Supreme Court of Justice, there are about 800,000 to one million abortions taking place every year amongst the population of women aged between 10 and 49. Of those, over 200,000 women were hospitalised in 2017 for complications resulting from the abortion, and there were over 5,000 serious cases. In 2016, there were 2 abortion-related deaths every two days, affecting mostly young women, black women and women with lower levels of education. While amongst white women the rate of unsafe abortion leading to death is of 3 per 100,000, this number rises to 5 for black women. Amongst those who only completed primary education, the rate is of 8,5 – almost twice as high as the national average of 4,5, according to 2016 data.

Despite this political context, in the year of 2018 the right to abortion also gained more centrality in political debates around the world, thanks to the relentless feminist struggle; in the Irish referendum which removed the “right to life since conception” from the Constitution; in the debates at the Argentinian Congress and Senate in favour of a comprehensive law on free abortion; and during the public audiences at the Brazilian Supreme Court which discussed the ADPF 442.

In a country where the majority of the population self-identifies as non-white, and considering our history, the fight for the right to abortion and for racial justice are everyone’s fight. Nonetheless, black artists are still being made invisible. In a interview for the journal Folha de São Paulo, Paulino reveals that she did not know about the work of the Cuban artist Belkis Ayón until a year ago; when both their artworks where displayed at the same exhibition in the Netherlands. Belkis was part of a group of Cuban artists who defied the paradigms of Cuban art in 1980, when they made the country face its African matrix roots. Similarly, a more recent Brazilian artistic movement brings this theme to the debate through the dimensions of police violence, gender, and racism.

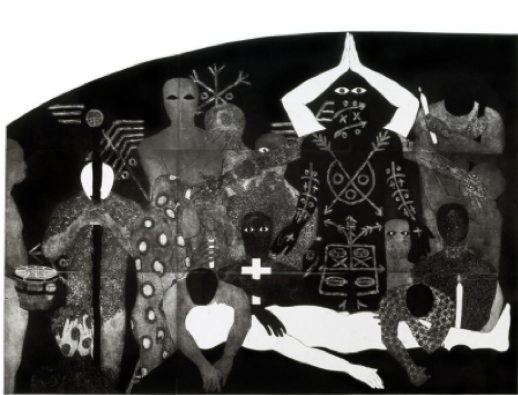

At a time of extensive re-Christianisation of culture and conservative backlash, Belkis’ art reclaim polytheist African cosmologies: a tradition from the secret societies of Ekpe and Ngbe from south Nigeria and Cameroon, which were brought to Cuba through slave trade and got preserved singularly by the secrete society of mutual support Abakuá, or Ecorie Enyene Abakuá. Belkis made her art a part of the rescue of these cultures in a transgressive manner. She turns upside-down the history of a secret masculine cult to rebuild Sikan’s trajectory, a feminine icon whose freedom is forbidden in the myth of Abakuá. By doing so, the artist describes the ambiguities and different forms of oppression of a patriarchal society, which brings us back to the political context and the motto of Paulino (read more about the artist).

Images

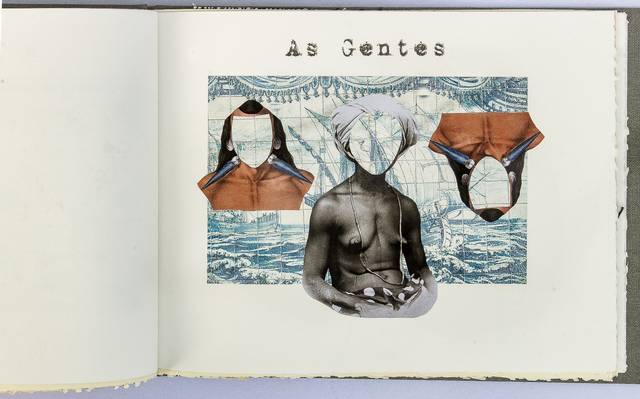

Rosana Paulino: Parede da memória, 1994/2015, Bastidores, 1997, Assentamentos, 2012, ¿História natural?, 2016.

Belkis Ayón: Nlloro, 1991; Mokongo, 1991.