Originally from A paper bird. Posted on 18 April 2015

So they’re going to deport gay foreigners from Egypt. My phone started ringing a few mornings ago, reporters wanting comments: solicitous but always with a subtext of What’s going to happen to you?

So they’re going to deport gay foreigners from Egypt. My phone started ringing a few mornings ago, reporters wanting comments: solicitous but always with a subtext of What’s going to happen to you?

I don’t know. The case involves a Libyan student whom police expelled from Egypt in 2008, after a complaint that he was gay. From back in Libya, he sued. This Tuesday, after seven years – the alacrity typifies Egyptian justice — an Adminstrative Court ruled that the Ministry of Interior did the right thing, under its power to”prevent the spread of immorality in society.” In fact, then, this isn’t a new policy. The court reaffirmed authority the state always had. Two years ago, for instance, a Polish citizen was vacationing on the North coast here with his Egyptian partner. The Pole grew seriously ill and had to be hospitalized. The nurses found their relationship suspicious and called the police. After several days under arrest, the Egyptian was freed; police deported the Pole, who was still in agonizing pain. I heard all about it at the time, but there was nothing we could do.

Things are much worse these days under Sisi. I sometimes seem insouciant about threats in Egypt, but I’m not. iI’s just that the atmosphere of threat is general here. It affects every corner of your personality, yet it’s hard to take it personally, so wide is the danger spread. Here’s a story. Yesterday, talking with a reporter in the usual seedy Cairo café — a place I’ve always considered safe — I saw a well-dressed man at the next table listening intently. Finally he interrupted. He gathered I was interested in human rights, he said. What did I do? Did I work for Freedom House? Freedom House is, of course, a banned organization, its local office raided and shuttered by the military regime back in 2011. I said no. He added, almost enticingly, that he himself had been tortured, and offered to show me his scars. I gave him my contact information and told him to call me. That was simple responsibility – you do not refuse a torture victim anything you can give; but afterwards I cringed inside. It’s how things are in Egypt. Other people, foreign passport-holders among them, have been arrested for “political” conversations in public places. You don’t know if the person who approaches you is victim or violator, survivor of torture or State Security agent; or both.

That suggests more clearly than any headline how Sisi’s regime is achieving totalitarianism – something Mubarak’s clumsy and inept authoritarian rule, his iron fist of five thumbs, never managed, perhaps never imagined or tried. I see now that totalitarianism is less comprised in how the state controls your private life than in how you do. Ordinary emotions such as sympathy or compassion cease to be modes of solidarity and become dangerous betrayals, self-revelations to be regulated with sleepless scrupulosity, as though they, and not the people you suspect, are the real informers. Mistrusting yourself comes first. Mistrusting others is merely the consequence. But the self-hatred self-suppression brings – and I hated myself for my fear – demands other objects, a wider field of play. To be foreign to yourself is to apprehend foreignness all around you, to fear the stranger in the land of Egypt.

Still: this story, the deportation story, went viral abroad. It’s strange because LGBT Egypt has not been in the international news much for months. When you deal with the media, you get used to its collective movements, puzzling as tidal motions when it’s too cloudy to see the moon, or the startled shuddering of gazelles racing in unison through tall grass. But other terrible things happened here recently. A man acquitted on charges of homosexuality tried to burn himself to death in despair. Police arrested an accused “shemale,” splaying her photos on the Internet. Egypt’s government threatened to close a small HIV/AIDS NGO because it gave safer-sex info to gay men. None of these got such press. The contrast is striking.

I learn three things from all this. First: our attention span isn’t what it used to be.

The world is everything that is the case, said Wittgenstein. These days we can click instantly on every fact about the world. When everything is the case, nothing might as well be; the excess of fact turns fantastic, the surfeit of reality becomes unreal. The LGBT arrests in Egypt had their moment of fame late last year, but the spotlight moves on; nothing is ever serious enough to make it halt. I’m not complaining about the press. In fact, many reporters have written about LGBT Egyptians both repeatedly and well (Lester Feder, Bel Trew, and Patrick Kingsley have helped keep pressure up, among many others). But the attention span of news consumers, and activists among them, shrivels; and that’s a problem.

I often think of the long international campaign throughout the 1990s to repeal Romania’s sodomy law. A few Romanian friends and I started researching the fates of people arrested under the law after I moved to the country in 1992 (it was some of the first human rights documentation ever on the persecution of LGBT people). Bucharest finally repealed the law in 2001. Over those nine years the Council of Europe and the EU exerted pressure; so did international groups like IGLHRC and Amnesty; and so did activist circles from Soho to Rome. The agitation was steady, so persistent that every time a Romanian politician visited Western Europe he was sure of facing a noisy protest somewhere. It would be simply impossible to keep a decade-long campaign like that going today. Nobody has patience. These days, if the law didn’t disappear after a single summer of sign-waving, the anger would evanesce like early frost.

Consider the transient 2013 furor against Putin’s homophobia: with its boycott calls and Stoli dumps, the campaign survived all of seven months. None of its self-proclaimed leaders even remember it anymore. Abstaining from vodka for a few weeks had absolutely zero chance of making the Russian state back down. Seasonal activist infatuations are doomed. Repression doesn’t cower before fads. Change takes work, and work means the long haul.

There is of course the well-known malady of “compassion fatigue,” a multisyllabic way of saying boredom. There’s been so much news from Egypt since the 2011 Revolution, so many twists in the plot, that even the most rapt listener gets lost. And isn’t the Middle East mixed up anyway? Six months ago, the enemy was the demon ISIS in Iraq. Now it’s the demon Houthis (who?) in Yamland or somewhere. Even the demons can’t keep themselves straight.

In fact, the confusion of cable news feeds the wiles of statesmen. “Compassion fatigue” serves a political end. Empathy, souring into self-pity about how overstrained it is, ignores inconvenient crimes. Egypt, by publicly killing “terrorists,” has planted itself on the side of the West. It’s best for all concerned to have minimal publicity about Egyptian state terror. After all, ISIS is worse — though they may have slain fewer civilians than Sisi. The Houthis are worse — though don’t they sound like they’re from Dr. Seuss? (And the distinction between being killed in Tikrit and killed in Tahrir Square may well look like the narcissism of small differences if you’re the one dead.) You might possibly remember Shaimaa el-Sabbagh. Activist, journalist, poet, mother, she was murdered by security forces in Tahrir in January, while trying to place flowers in honor of the now-expired Revolution’s martyrs. A photograph of her dying in a friend’s arms broke through the wall of indifference; the story briefly travelled worldwide.

Last month the state pressed criminal charges. No, not against her killers. Against the witnesses who testified to prosecutors about her killing — because they’d joined an “illegal demonstration.” They could face five years in prison, for being there when Shaimaa was shot. Did you know that? No. The story’s over; we’ve moved on. It’s better you don’t know, because after all, your compassion might get tired; wiser to tend your valetudinarian emotions than defend exhausted dissidents, or the memory of those already murdered and past help.

Another lesson is: some people don’t count. Sex workers, for instance. I hate to say this, because it seems to give the Egyptian government a pass – but the idea that governments can exert moral controls at the border is not a Middle Eastern peculiarity. The US still denies entry to anyone involved in sex work. The American immigration bar on “moral turpitude” uses almost the same language as the Egyptian exclusion. Most gay Americans have no idea of this: because the American gay movement couldn’t give a shit about sex workers.

And then there are trans people. Most of the Egyptians arrested in the crackdown since 2013 were transgender. The government explicitly says it’s going after “she-males,” sissies, mokhanatheen. Nonetheless, most coverage by Western media – or by Western NGOs – talks about an anti-“gay” crackdown, as though sex were everything, gender irrelevant, and trans folk distractions from the main event.

The Egyptian arrests that got the most publicity were ones that did involve cis men: working-class clients of a bathhouse, or respectable bearded types doing the gayest of gay things in Western eyes, getting wed. In Egypt, as a colleague of mine points out, these gained extra-large headlines because they showed “perversion” at its most dangerous, infecting people like us, not just the pre-emptively anomalous. But they became poster boys in the West for similar reasons, because these were people gay readers could identify with, muscular and married, “normal.” Trans people doing sex work are neither nice nor news. Who gives a damn? Getting arrested is simply their destiny, their job.

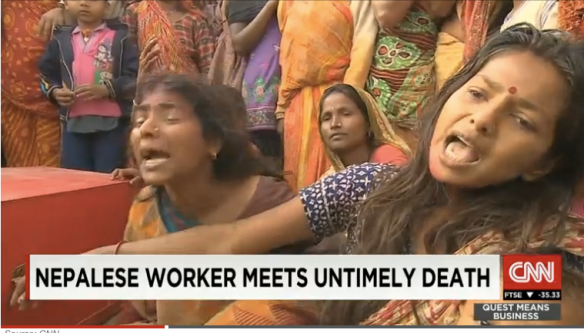

In 2013 the Western press started reporting that the Gulf Cooperation Council countries – Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia – were going to test and expel “gay” people at the border. There was a storm of stories about how dumb this was. Silly Arabs, setting up gay detectors in airports! Then it turned out the targets weren’t gay people (or Western visitors) at all. Kuwait had proposed chromosome tests for migrant workers, to determine if their genes and their IDs conformed. They meant to expel trans people coming from countries like Nepal (a major exporter of exploited labor to the Gulf) that now permitted them treacherously to change their passports. This wasn’t silly; it was scientific, and a much worse invasion of privacy than an imaginary gaydar machine.

And with that, the stories stopped. Nobody cared about trans people – or poor Nepalis. The Human Rights Campaign, the US gay behemoth now going international, still claims in a recent report that the tests were meant to keep out only “gay” people. This isn’t a mere mistake; HRC knows better. But their members’ empathy, and donations, won’t get revved up for trans Nepali domestic workers. Purely hypothetical Western gay businessmen facing persecution, blond boys flying first class and unfairly driven from Abu Dhabi like Sarah Jessica Parker, are way more likely to stimulate the cash flow.

And that shows a third lesson. Some people do matter. Some stories do break through. There are more important travelers than migrants or refugees. This story has legs because it implies that tourists, innocent people from the West, can be swept up in Egypt’s series of unfortunate events.

Sometimes tourists are victims of rights violations, and that must be condemned. But the most effective condemnations draw connections. What Westerners endure can bring attention to what others suffer.

In mid-2013, after the Egyptian coup, queer Canadian filmmaker John Greyson and his colleague Tarek Loubani were arrested in Cairo. They were “tourists” in a broad sense, passing through on their way to work in Palestine. The paranoiac regime, which treats all real or imaginary opponents as terrorists, accused them of conspiracy. The international campaign to free them, politically astute, brought into focus the violent repression Sisi also inflicted on many others, including massacres of Muslim Brotherhood adherents. (A mark of how successfully Greyson’s and Loubani’s case illuminated Egypt’s whole human rights record was how they pissed off Canada’s equally terrorist-obsessed right wing.) And Greyson has passionately kept on doing so since his release.

On the other extreme, I have miserable memories of the embattled gay pride in Moscow in 2007. A flock of foreigners came, European politicians and minor celebrities, many hoping to garner a little publicity for the cause and themselves: get arrested briefly, spend an afternoon in jail, give a press conference. It was no more intrinsically offensive than taking selfies at Bergen-Belsen. They inadvertently drew the media away, however, from the young Russian marchers arrested at the same time, sent to jail in the Moscow outskirts with no cameras attending. They also monopolized the lawyers; the young Russians had none. I’m afraid the Moscow Pride circus is more typical of what happens when Westerners get involved than was John Greyson.

Nicholas Kristof, white-savior-in-residence at the New York Times, has written how nobody cares when he just describes foreign brown folks and their strivings. It takes a “bridge character,” “some American who they can identify with,” to “get people to care”:

It hugely helps to have appealing and charismatic characters … Often the best way to draw readers in is to use an American or European as a vehicle to introduce the subject and build a connection.

But it never works. Read Kristof and see: all the sympathy goes to the span itself, to the charismatic white connecting hero. Nobody’s attention makes it to the other side. Whatever happens to me, in Egypt or anyplace else, God save me from being a bridge to nowhere.

And here’s the heart of the matter. The context for this latest case is twofold. Egypt’s government has been cracking down on gender and sexual dissent for a year and half. But it’s also been whipping up xenophobia, fear of foreign influences, hatred of foreigners themselves. Now it’s figured out how to make those two kinds of incitement meet.

Westerners have been targets of Egypt’s xenophobic campaign, painted as conspirators against the country. Michele Dunne, an American expert on Egypt, was turned away at Cairo airport in December in retaliation for her criticisms of Sisi. Ken Roth of Human Rights Watch was expelled last August. Last month the government announced it would stop granting visas on arrival to most Western visitors, requiring applications in advance instead. It was a move to keep unwanted critics out. But Egypt understands how vital its already-moribund tourist industry is, and how restricting visas might scare the last few pocketbooks away. The measure was “postponed.”

Although this deportation case dates back seven years, the way the government is publicizing it now – while it’s arresting alleged LGBT people on a massive scale – suggests they have new plans to put these powers to use. The truth is, though, that Western tourists won’t be the easiest targets. Those who’ll suffer most will be from poorer African or Arab counties, those who don’t spend dollars, whose embassies won’t lift a digit to defend them: or – still more defenseless — suspected trans or gay people from Egypt’s communities of refugees.

Some Middle Eastern states have been welcoming to refugees. Syria – though one of the poorest countries in the region – took in waves of displaced Palestinians from the nakba till now, and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis after the Bush invasion. Egypt has not, on the whole, been on the hospitable side. The national identity inculcated since the 1950s is intolerant of ethnic difference and of influences from outside. The state has accommodated refugees – Sudanese since the 1990s, Iraqis and Syrians now – but reluctantly; it harasses them, denies them political rights or permanent status, and insists it’s only a transit point for loiterers who eventually must move along. And ever since Sisi took power, refugees have been vilified by state-promoted xenophobia. Syrians and Palestinians are especially singled out. But every refugee in Egypt lives in anxiety. There are plenty of LGBT folk among them. (Last fall a cohort of plainclothes security forces raided the apartment of a gay Syrian refugee I know. They searched his papers, computer, phone, and noted all the gay-related documents and photos. They didn’t arrest him. They just wanted him to know they were there.) This publicized decision will only sharpen their fear.

The fate of refugees in Egypt is not just abstract for me. It’s bound up with guilt. In 2003, working for Human Rights Watch, I lived in Cairo for several months. Two days after I arrived, police began arresting refugees, mostly African, in sweeping raids in neighborhoods where they clustered. Such harassment is recurrent; most were freed in days; but, covering the raids and talking to the victims, I got to know some of the community leaders. In the next months, they organized many meetings for me with refugees in Cairo, so I could hear their stories. I thought perhaps the documentation could push Human Rights Watch into reporting on the situation in detail.

Most of the people I talked to were South Sudanese, survivors of the civil war raging there for 20 years. We met in their cramped flats; in the dusty courtyard of All Saints Cathedral in Zamalek, an asylum where police rarely intruded; or in rundown Coptic churches in Shobra, where fellow Christians had afforded the South Sudanese some space.

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) office in Cairo was and is one of the slowest in the world. It could take UNHCR years — it still does — just to schedule an intake interview. Until the UN formally recognized them as refugees – three, five, seven years after their arrival – the displaced had no legal rights in Egypt at all; after that, they had to wait more years for the UN to resettle them in a third, safe country. Some had been in Egypt for well over a decade. Meanwhile, they endured constant harassment, joblessness, humiliation. Nobody outside the community had listened to them before. Women working for a pittance as maids told me about sexual harassment and rape. Some men sold their organs to survive. Police picked them up off the streets, beat them, ignored the UNHCR’s hapless interventions to protect them; there were stories that some refugees, randomly arrested, had been driven south and deported illegally back across the border, to Sudan and death. The waiting and fear drove some people mad. One courtly man of about fifty took me aside at a church meeting. He had been tortured in Sudan; he showed me a scar on his arm. He had many narratives of persecution, but most embarrassing now, he said was an unbearable rumor circulating all across Egypt that he had a tail. He showed me medical documents, testimonies elicited from doctors in English and Arabic, painfully certifying that he was tailless. He also gave me a typed personal statement, in English. “Among the many crosses I am compelled to Bear, in a long Journay and much Torture, the widespread libel that I am a Tail Wizard is completely Unfounded.” Others at the meeting treated him with deference, as if they envied the relief in his delusions.

I began to feel uneasy about these meetings. My presence was an implicit promise that I would do something, and there was nothing I could do. In February and March Egypt’s security state moved on to arresting and torturing hundreds of leftists opposing the Iraq war. I had to document that, and gradually my meetings with the Sudanese lapsed. Human Rights Watch, its refugee program stretched thin, never produced a report on these abuses (though in recent years they’ve documented, in harrowing detail, the monstrosities traffickers inflict on desperate African refugees in Sinai). I still think of my inability to provide some concrete assistance as one of the worst failures in my twenty-five year career, and I can’t remember it without shame.

Now there’s another basis, inscribed in law, for harassing some of them.

Some refugees tried to speak up about their endless agonies. Two and a half years after I left, in September 2005, Sudanese started a sit-in before the Cairo UNHCR offices, demanding faster processing of their claims. The UN treated the protest with contempt; one staffer accused them of wanting “a ticket to go to dreamland.”

Three months passed; then UNHCR called in the authorities. On December 30, 4000 police surrounded and shot at the unarmed Sudanese. At least 27 died, including eight women and between seven and twelve children. Thousands were arrested; among those, hundreds who had not yet been given refugee cards by UNHCR faced deportation. The first dozen Cairo planned to deport included three women and a child. “Egypt has dealt with the sit-in of the refugees with wisdom and patience,” the country’s foreign minister said.

Ten years later, this massacre is forgotten in Cairo. It never figures on the list of Mubarak’s crimes. Nobody bothers to remind UNHCR of its complicity in the killings. Refugees don’t matter.

The massacre did merit brief mention in a text that’s become a Bible for right-wingers warning about the Muslim peril. Reflections on the Revolution in Europe: Immigration, Islam, and the West is a 2009 book by conservative American journalist Christopher Caldwell. Seemingly ignorant that the demonstrators were Christian, he uses the protest to press his case — distorting it, insulting the dead in the process:

3000 Sudanese camped in front of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Cairo to seek refugee status. What was bizarre was that many of them already had refugee status in Egypt. So these were bogus petitioners in the sense that what they were really seeking was passage to some country more prosperous than Egypt. The sad ending to the story, though, shows that the line between “real” and “bogus” calls for help is not always easy to draw: in the last days of 2005, Egyptian riot police attacked the encampment, killing twenty-three [sic].

That’s not true. Either Caldwell, who claims to be an immigration expert, doesn’t understand refugee law, or he’s just lying. I think he’s lying. Egypt doesn’t grant anybody “refugee status.” It has no national asylum procedures at all. It gives people whom the UN recognizes as refugees (the status most of the the protesters were still waiting for) a limited right to stay, but only temporarily, on the understanding they will eventually be resettled elsewhere. The dead Caldwell defames were not “really seeking” someplace “more prosperous.” They were asking the UN to do its mandated job, to find them a country that would give them the legal right to live.

Caldwell is a fool, but he’s right on one thing: this is all about the bogus and the real. It’s about belonging. Egypt’s government is now deciding who belongs or not, who’s a real or bogus person. The gays are fake people, void of the authenticity and weight that might entitle them to stay.

But isn’t that how we readers, sympathizers, citizens use these stories too, to separate the wheat from chaff? We winnow the fit objects of our concern from the unwanted ones, from those whose sufferings don’t ring true because we don’t recognize ourselves in them. Tourists count, not migrant workers. White travelers count, not brown refugees. Gay, yes; transgender, no. We each mistrust the incomprehensible stranger, you as much as I do. We were all strangers once in the land of Egypt. But we forgot.