Originally published on Paper Bird on 28/09/2015. Available at: http://paper-bird.net/2015/09/28/anusbook-forensic-exams-tunisia/

by Scott Long

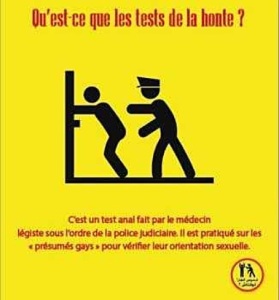

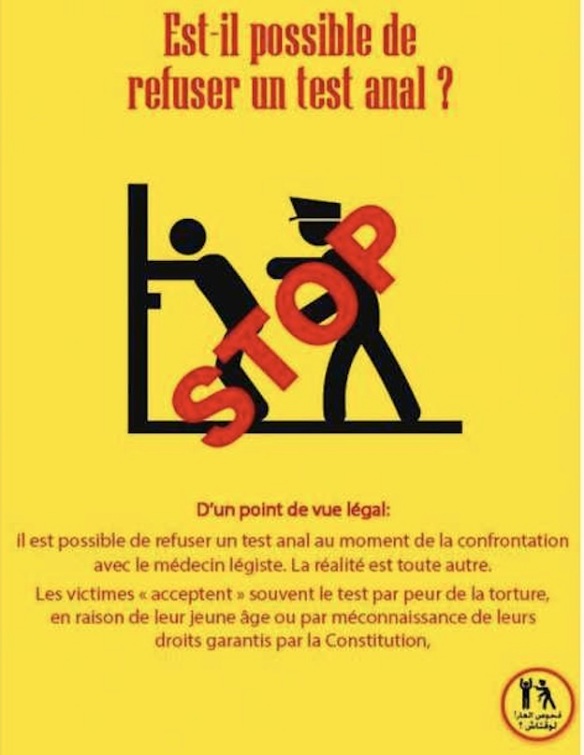

“Tests of shame! Till when?” Campaign by the Tunisian group Damj

Join the campaign to end forced anal tests in Tunisia. You can start by posting a message of support, or even re-posting this article, on Twitter or Facebook. Paste in the hashtag #لا_لفحوصات_العار (No test of shame!), or #لا_للفصل_230 (No to Article 230!); or use the hashtags #TestdelaHonte and #Tunisie.

On September 6, police summoned a young Tunisian man, 22 or 23, in the coastal city of Sousse. One of his friends had been murdered; the man numbered among the contacts on the victim’s phone. Someone in the young man’s circles told me:

A friend of mine was there in the police station to be with him in case he needed any thing. This friend told me that the arrested young man was being beaten as he was interrogated. Also, he had no legal representation at all. I was told that the police checked Facebook conversation with the murdered man and based on them they charged him with homosexuality. The[y] could not find any links with the murder so they decided to charge him based on the anti-sodomy law in Tunisia.

The young man later told AFP, through the attorney he’d finally been able to reach, that “I do not understand why I have been sentenced … or why I was detained for six days without being allowed to contact my lawyer … I want to get out and resume normal life. I don’t know what I’ll do with my studies and my work. I do not want to be rejected by society,”

Unfortunately, these abuses on arrest are standard practice in Tunisia; the law allows police to hold defendants for up to six days, without access to lawyers, before a judge or prosecutor sees them. A United Nations expert condemned this in May as “counter to the right to a fair hearing, the right to defence and the right to have access to legal counsel … The excessive length of police custody combined with the fact that a suspect does not have access to a lawyer may create the circumstances for ill-treatment.” On September 11, he was sent to a prosecutor, and four days after that to a judge, who ordered an “anal inspection” — a forensic anal examination, inflicted without his consent. The examination found him “used’; on September 22, the judge sentenced him to one year in prison, under Article 230 of the Penal Code, which punishes “sodomy” with up to a three-year sentence.

The story stirred up a storm in Tunisia because it exposes two ongoing scandals. One is the persisting criminalization of private,consensual sexual acts. The other, deeply connected, is the state’s invasion of the body, an incursion of which the anal tests are an extreme but indicative form. As Yamina Thabet, president of the Association Tunisienne de soutien des minorités (Tunisian Association for the Support of Minorities, ATSM), declared on Twitter, the case sent a citizen to prison “based on a liberticide law and using abusive evidence.”

Damj, a Tunisian NGO fighting to decriminalize homosexual conduct, swiftly launched a campaign to educate the public about the “tests of shame” — which its president, Baabu Badr, described as “a surrealist practice in today’s Tunisia.” The leftist party Al Massar declared the tests “inhumane and unacceptable” and the trial “a danger to the democratic processes of the Second Republic.” ATSM said the exams “recall the practices of the Inquisition.” Wahid Ferhichi, president of the Association pour la défense des libertés individuelles (Association for the Defense of Individual Liberties) complained that “The consent of the accused should be required for this type of test but in fact, the suspect is put under pressure. His refusal is held against him as a presumption of guilt. But the law stipulates the presumption of innocence, and not the opposite.” And Médecins contre la dictature (Doctors Against Dictatorship) called the exams “a blatant attack on physical integrity which falls under the framework of physical torture.” It said they violate Article 23 of Tunisia’s progressive new constitution, which holds that “The state protects human dignity and physical integrity, and prohibits mental and physical torture.”

Unquestionably the exams are torture. They prove nothing and have no medical basis, though their obsessed practitioners try to believe they do. Their only real function is to resemble rape, to hammer home the victim’s helpless abjection before pitiless power. (The fact that, in Muslim countries, prisoners are often told to assume the posture of prayer as the exam is inflicted only lends a blasphemous twist to the humiliation.)

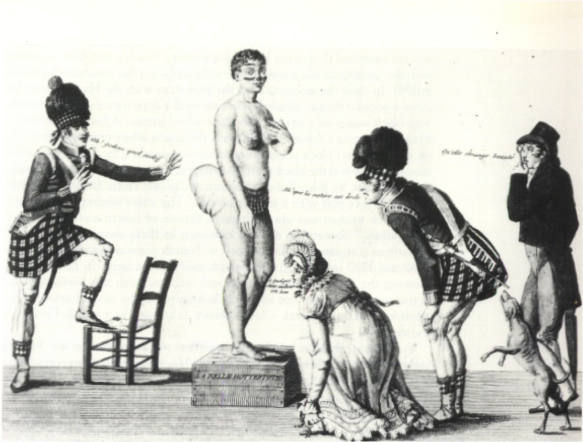

I’ve studied these tests for more than ten years; the article I wrote on them for the Journal of Health and Human Rights is still pretty much the only historical analysis of them around. They grew from the theories of a 19th-century French forensic doctor, Auguste Ambroise Tardieu. Tardieu studied both prostitutes and “pederasts” through the peculiar lens of a pornographic imagination. He believed that vice left physical evidence on the body — that through these stigmata, doctors and police could detect the adepts of perversion, however cunningly they concealed themselves in urban anonymity and confusion. The “pederast” carried six unmistakable marks: “excessive development of the buttocks; funnel-shaped deformation of the anus; relaxation of the sphincter; the effacement of the folds, the crests, and the wattles at the circumference of the anus; extreme dilation of the anal orifice; and ulcerations, hemorrhoids, fistules.`” Among these the conical anus was “the unique sign and the only unequivocal mark of pederasty.” Tardieu launched generations of forensic pseudoexperts on an idiotic quest to detect suspect anuses shaped like trumpets, pyramids, or calla lilies. I first read Tardieu in my room in Cairo back in 2003, like a dirty novel, in a copy downloaded from the digitized collections of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. I shuddered in disbelief that doctors could credit this kind of fantasy; except by that time I’d already talked to the doctors who performed the exams in Egypt, and I knew.

Tardieu’s ideas were discredited in much of the West by the twentieth century — partly on pure scientific grounds, partly because, as the ideal of universal citizenship became an essential prop of government, the idea that certain bodies were palpably, legibly deviant or illegal stopped being a tenable approach to politics or crime. (Two facts can be said to symbolize the qualified victory of that universal ideal, one well-known and one almost forgotten. On the one hand, the slow triumph of women’s suffrage meant that sexual difference cased to be a comprehensive legal disqualification from the public sphere; on the other, the British feminist campaign against forced medical testing of suspected prostitutes — so-called “specular rape” — asserted that the state couldn’t use medicine to winnow respectable from “fallen” women in that public world.) Of course, the belief that some bodies were scientifically identifiable as dangerous never wholly went away. It was intrinsic to fascism. It’s implicit in contemporary American penology, where to be young and black is to have a prison sentence written on your forehead.

However, Tardieu’s specific delusions about sex and the body are largely dead in the Europe from which they sprang. They survive, instead, in the countries Europe colonized. In addition to the Middle East, where they run rampant, they’ve been documented across large parts of sub-Saharan Africa. There’s a reason. The promise of universal citizenship wasn’t valid in all locations. It was fine for the West, but in the subject territories, the colonial powers practiced divide and rule. Their authority was made through measuring and classifying bodies — by race, ethnicity, sex, health, height, malleability, morality, cleanliness. The law against “sodomy” in Tunisia dates back to a 1913 criminal code the French authorities imposed; homosexual acts had been legal in metropolitan France since the Revolution, but in the Maghreb the penalty was resurrected — to segregate immoral elements in the population with a view to purification and control. Public health was another great fixation of colonial authorities, British and French alike. (It was one of the few areas where Victorian British intellectuals were willing to take French tutelage.) Through its emerging discourses, they aspired to disinfect indigenous physical filth with the aseptic, separating order of reason. Exported extensively on French and British warships to the warmer climates of the world, Tardieu’s theories about lily-shaped assholes found room to flower; they gave colonial governments the snug belief they could actually measure native perversions with a ruler — and could subject those bodies to scientific domination. The illusions that powered the colonial state became the post-colonial state’s inheritance. Governments still cling to the strategy of division, the distrust of universality, the corporeal ambitions of authority, and the myths that underpinned them. Under precarious, authoritarian regimes struggling to manage and moralize unruly, prolific populations, Tardieu lives.

Tunisia was, of course, where the Arab Spring began. It’s still the one state that’s stayed, however haltingly, a democratic course while the others lapsed into civil war or the Ice Age. Lisa Hajjar argues that a “torture trail” ran through the 2011 revolutions: people came together in revolt partly because they shared a loathing, cutting across classes and identities, for regimes that secured their rule by brutalizing and destroying bodies. Resisting state power over the individual body was a key flashpoint in many countries: in Egypt, for instance, the “We Are All Khaled Said” movement roused people in transformative solidarity with a single middle-class youth tortured and murdered by police. Tunisia was at the heart of this. Its revolution ignited when Mohamed Bouazizi, a street vendor, put his body literally on the line against the state by burning himself to death, to protest police violence and bureaucratic indifference. The question of corporeal resistance, freedom in the bone, has remained central in Tunisia since. It underlies the controversy over society and state’s collusion in enforcing women’s virginity before marriage — the splendid film National Hymen makes clear how this isn’t just a question of “individual freedom” in the abstract, but of the nation’s claim to illegitimate rights over the body. It’s not surprising that progressive activists in Tunisia should understand the forced anal exams — an assertion of the state’s power over every carnal crevice of your person — as a crucial battle in this elemental war.

It’s sad and telling that the young man’s ordeal began with the police searching through Facebook messages — that technologically modern method of rooting out private evidence. In his misery, two forms of surveillance met. Like Tardieu’s theories, Facebook claims it can make social networks legible. The fear that haunted Tardieu was people copulating secretly, flouting class and status, outside society’s panoptical scrutiny, promiscuous and unrecorded. As I wrote in 2004:

To Tardieu, “habitual pederasty,” a tendency outwardly often undetectable, had infiltrated all social classes. His aim was to help justice “pursue and extirpate, if possible, this shameful vice.” His obstacles were the slippery masquerades in which a protean pederasty hid. He warned of “habitual pederasty among married men, among fathers of families.” The treacherous skill by which pederasty concealed its public marks lent urgency to the “precise and certain declaration of the signs which can make pederasts recognizable” – pinning down the tendency’s spoor upon the skin itself.

That’s what, in a very different register, Facebook promises: to reveal selves and networks. It will render your desires and connections visible, to your friends but also — the fine print of the bargain — to companies hunting customers, and to governments tracking crime.

The cops start with trailing you in the cyber placidity of Facebook. But there’s an Anusbook they want to study, too, and it’s violent, not virtual. Surveillance begins by intercepting words; it ends by invading bodies. The state monitors messages at first, but only the better to torture their makers. Knowledge is the means, but the goal is pain. Social media make up a dull, expository prologue. The intricate exposed agony of your wounded body is what the police really long to read.

Source: http://paper-bird.net/2015/09/28/anusbook-forensic-exams-tunisia/