On the eve of the 2018 International AIDS Conference that takes place in Amsterdam (Netherlands) in July, the Global Public Health Journal, one of the main academic publications on global public health, released its latest volume “Special Symposium: Critical Perspectives on the ‘End of AIDS”, an issue that reunites a collection of articles on the too optimistic belief that the AIDS epidemic is set on a horizon that will, by 2030 or very soon, come to an end. Edited by the renowned international experts Nora Kenworthy, Matthew Thomann and Richard Parker, this publication aims to promote real accounts in order to undermine the rhetoric on the end of AIDS, as well as empirical evidence on the current state of the art of these political slogan efforts. For its purpose, this endeavor favors the diversity of places and populations who are usually at the margins of mainstream studies, part of the “End of AIDS” project.

Assigning a project status, as the authors do, serves the purpose of conceptualizing a body of “discourses, practices, contexts and policy landscapes” that have been under scrutiny of a historic and critical analysis on this Special Symposium. And, in order to fill the gap between what takes place at the rhetoric of the biomedical science discourse heights, that promote the end of AIDS, this volume benefits the accounts of those who are at the ground of this political conflict, based on social science and public health evidence.

First, the article From a global crisis to the ‘end of AIDS’: New epidemics of signification (Kenworthy, Thomann & Parker) grants us a thorough examination of the discursive and political turn about AIDS, having as elements for analysis the philanthropic and political interests that are underlying to the prevalence of biomedical and short-term responses and to the global field of changing institutional relations.

Subsequently, the article The ‘end of AIDS’ project: Mobilising evidence, bureaucracy, and big data for a final biomedical triumph over AIDS(Leclerc-Madlala, Broomhall & Fieno) investigates the circumstances that led to the temporal divide between the former policy that invested on ‘best practices’ to face up to the epidemic and the current established short-term strategy that marks a biomedical solution win over the AIDS politics.

Then, Chronicity, crisis, and the ‘end of AIDS’ (Sangaramoorthy) challenges the terminal aspect trusted on the AIDS epidemic by the popular end discourse with accounts from less resourced areas, such as the US South and east and southern Africa, that emphasize the true long temporal aspect of the infection, still marked by precariousness.

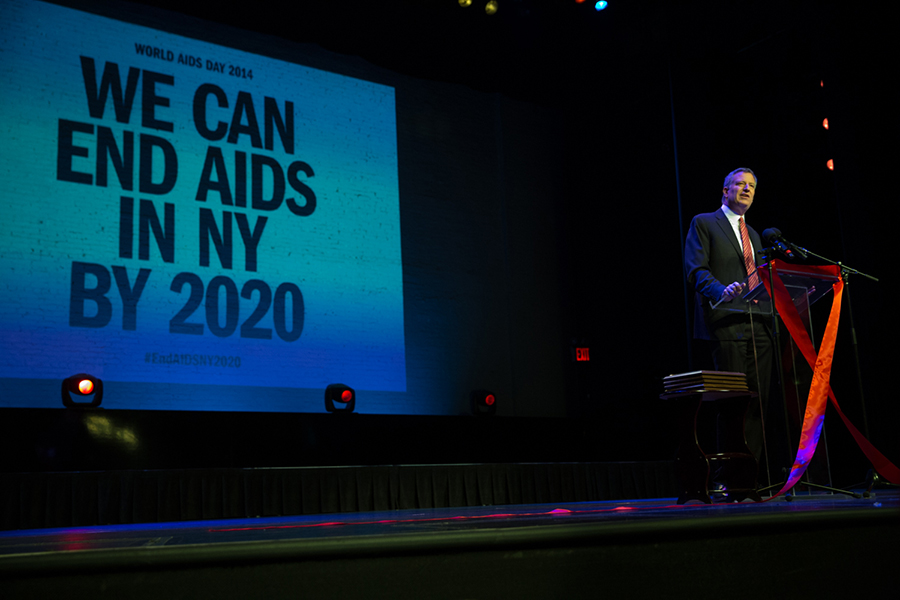

The fourth article ‘On December 1, 2015, sex changes. Forever’: Pre-exposure prophylaxis and the pharmaceuticalisation of the neoliberal sexual subject (Thomann) analyses the PrEP campaign in New York – central to the wider strategy of the End of AIDS project that aims to prevent individuals from becoming infected and that neglects people who live with HIV/AIDS – and its underlying promotion of a neoliberal subject, who becomes entirely accountable for his/her sexual prevention.

Lastly, in the fifth article Queering the evidence: remaking homosexuality and HIV risk to ‘end AIDS’ in Kenya (Moyer & Igonya), the authors write an ethnographic work to critique the current policies in Kenya that target especially male sex workers – men who have sex with men in a broader category of Key Populations – and, as consequence, this group is granted responsibility on the problem of HIV prevalence in the country, which overlooks complex matters, such as the economic and psycho-social problems experienced by male sex workers.

This body of literature plays a significant role in the current political landscape that precedes the 2018 International AIDS Conference and proposes a critical and fine regard of what lies beneath — interests, politics, moral, economy — the hollow promises from high institutions that fail to look down.