INTRODUCTION: Sexual and reproductive rights

at the 2012 Universal Periodic Review of Brazil*

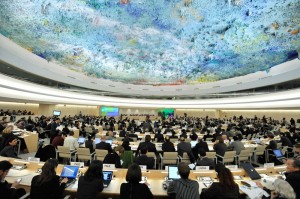

In May 2012, Brazil was submitted to the second round of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations (UN-HRC), the first round having occurred in 2008. In both occasions, the review was based on three different sources: data presented by the official report produced by the Brazilian government; a report organized by the High Commissioner of Human Rights; and a number of shadow reports written by civil society organizations. The recommendations made by UN member states that participated in the Brazil 2012 UPR were based on these different reports, but also on information collected by diplomatic bodies. At this meeting when Brazil reported, member states countries of the UN-HRC asked questions, which were answered by the Brazilian government delegation in Geneva and then the countries presented written recommendations. It has been also defined that, the latest by September 20th, Brazil should inform the UN-HRC on what recommendations would be accepted, what would be partially accepted and what would be rejected until 20 September 2012.

In May 2012, Brazil was submitted to the second round of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations (UN-HRC), the first round having occurred in 2008. In both occasions, the review was based on three different sources: data presented by the official report produced by the Brazilian government; a report organized by the High Commissioner of Human Rights; and a number of shadow reports written by civil society organizations. The recommendations made by UN member states that participated in the Brazil 2012 UPR were based on these different reports, but also on information collected by diplomatic bodies. At this meeting when Brazil reported, member states countries of the UN-HRC asked questions, which were answered by the Brazilian government delegation in Geneva and then the countries presented written recommendations. It has been also defined that, the latest by September 20th, Brazil should inform the UN-HRC on what recommendations would be accepted, what would be partially accepted and what would be rejected until 20 September 2012.

The UPR is a dialogical or collaborative process. This format was established after the creation of the UN-HRC, in 2005, in order to reduce the tensions that have always characterized intergovernmental debates on human rights. To illustrate that suffice to remind that quite often what was named as “excessive politicization” by various member states has paralyzed the work of the Human Rights Commission, which was the overarching human rights political body preceding the HRC. In this new format, all member states are reviewed every four years. The states that are being reviewed may or may not accept the recommendations, but when refusing them, they must explain why. The process also supposes that when recommendations are accepted they will be implemented, as a commitment assumed by the state under review, which is also supposed to periodically inform the HRC on the implementation. The UPR processes was designed to ensure the human rights situations is reviewed in all countries, in ways that restrict the possibility of unilateral accusations and dilute political tensions that more than often compromise the human rights debates in global arenas. This has many positive sides, but also caveats. Very clearly when states assess the human rights realities of other states these evaluations are not always as sharp, technically precise and independent as those performed by treaty body and special rapporteurs.

Another crucial aspect to be considered when assessing the results of the last Brazil UPR are the conditions prevailing at the current geopolitical scenario: the persistent economic crisis in the United States and Europe and the parallel emergence of the new global powers — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — constituting the new dominant economic poles, or the so-called BRICS. The geo-economic and political factors that explain the BRICS emergence are multiple and too complex to be analyzed here. Yet it is important to note, in this context of analysis, that as Brazil repositions itself as an emerging power in the global scenario the ways in which countries — North and South of the Equator — perceive Brazilian internal problems and policies and relate with the country in global arenas inevitably changes. This new perceptions and forms of relationship were evidently reflected in 2012 Brazil UPR process.

In the previous UPR, in 2008, Brazil was subject to several recommendations. One of them concerned, for instance, the approval of the Law on Access to Public Information that was pending in Congress, which was, in fact, approved in 2011, after a protracted debate in society and at Congress level. However, not all recommendations made during the first UPR round were as successful. Thus, in May 2012, Brazil was interrogated for not having presented periodical annual UPR reports, as it has committed itself to do in 2008. Questions were also raised in respect to “strong” recommendations made in 2008, as in the case of the creation of a national independent human rights institution aligned with Paris Principles. In this case, although a bill is pending in Congress that proposes the creation of a national council for human rights, the text under discussion is not harmonized with these international premises. Therefore, once again, in 2012, a number of member states would reiterate the same recommendation. In addition, new recommendations were made in relation to a wide range of human rights issues. While many countries have praised Brazil for its good performance as in the case of poverty reduction, some member states also pointed towards the persistence of grave violations of human rights, as in the case of prison conditions and torture, but also in regard to of gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive rights.

It is important to mention that the participation of Brazilian civil society in the 2012 UPR has greatly expanded in relation to the first round. This time, around 50 shadow reports – mostly produced by Brazilian civil society organizations, either individually or jointly – were presented to the UN-HRC. This wider civil society presence and greater vocality was crucial in the review process. The problems identified in their shadow reports contrasted with the image projected by Brazil today: a country that is overcoming poverty, solving the social problems and becoming a global player. On the one hand, the official report, by and large, emphasized the achievements of national public policies, in ways that fueled this image, without, however, offering substantive quantitative and qualitative data, as it would be required. On the other, the reports submitted by civil society organizations pointed to policy limitations and serious human rights violations. With regard to sexual and reproductive rights, the shadow reports presented have addressed: homophobic violence against LGBT people, especially in regard to the impunity of these crimes; censorship of educational materials on sexual diversity; problems observed in relation to the access to services and distribution of HIV/AIDS medicines; the criminalization of the HIV/AIDS transmission; violation of women’s rights deriving from the criminalization of abortion; restrictions to the access to drugs that reduce the risks of illegal abortion; and, persistent problems in prenatal and obstetrical assistance with negative effects maternal mortality rates [Click here to read the shadow reports written with the contribution of SPW and ABIA].

The contrast between the reports prepared by civil society and what the Brazilian government officially presented has not escaped the attention of several delegations that participated in 2012 UPR round. This contrast, however, is not directly reflected, however, in the 170 recommendations made to the Brazilian government. The strongest recommendations made in 2012 reiterate concerns arose in 2008 in respect to outstanding issues, such as autonomy of national human rights institutions, torture, the criminal justice and the public security systems and prison conditions. But a number of recommendations have also been made that, if accepted by the Brazilian government, could have deleterious effects on sexual and reproductive rights, such as the recommendation presented by the Hole See that requires Brazil to define the family as a union between man and woman, or the proposal made by Namibia to expand education religious in the public education system. Another recommendation that also raised concerns among reproductive rights activists was the one made by Colombia in its appraisal of the compulsory registration of pregnant women as a strategy for reducing maternal mortality. This particular policy guideline had, in fact, been subject to an intense debate at country level between January and May 2012 [Click here to read more on it]. Lastly, other recommendations if implemented may have very positive effects on sexual and reproductive rights, such as those made by France and Estonia regarding the further de-criminalization of abortion and measures to ensure the privacy of women in criminal proceedings. The same can be said of Finland’s proposal of a legislative reform to ensure marriage equality and that effective measures are taken to reduce and punish homophobic crimes.

To understand why certain recommendations regarding violations were more frequent and stronger, it is important to understand that classical human rights themes always capture more attention than emerging topics, such as violations of sexual and reproductive rights, or even violations related to development projects, as in the case of the of the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, or those perpetrated by multinationals, including Brazilian companies operating in other countries, areas that have also been covered by 2012 civil society shadow reports. Moreover, for the critical analyses developed by civil society organizations to be more thoroughly absorbed by the state actors engaged in the process, it is not sufficient to write and send shadow reports. It is essential to invest in a wide and systematic circulation of the information produced among member states, international networks and other UN bodies. Generally speaking the majority of civil society organizations, including those from Brazil, do not have the necessary financial resources, or sometimes the expertise, to perform these tasks satisfactorily. In contrast, the diplomatic missions of countries at the UN HRC have the capacity to permanently interact with other state members. In the case of the 2012 UPR, it is quite flagrante that the Brazilian mission has efficiently prepared the grounds for the review to be as sooth and positive as possible.

:: The 2012 UPR aftermath

While the Brazilian governmental delegation in Geneva was very numerous, only six representatives of Brazilian civil society have followed the May debates at the UN-HRC: Camila Asano and Mara Arizaga (Conectas Human Rights); Paula Martins (Article 19); Magaly Pazello (NUPEF Institute/Association for Progressive Communications); Luis Emmanuel Cunha (Gabinete de Assessoria Jurídica às Organizações Populares – GAJOP); and Alexandre Mapurunga (Coalition of organizations of persons with disabilities). After the formal review session, attending a request made by the Brazilian NGO Conectas Human Rights, the Brazilian mission convened an informal meeting with these representatives, the Minister of the Department of Human Rights, Maria do Rosário, and the Brazilian official delegation. On that occasion, the Minister has positively evaluated the process as well as appraised the recommendations made to Brazil. She has also indicated next steps to be taken as to ensure the unfolding of the UPR at national level:

- Creation of an inter-sectorial group to implement and follow-up how recommendations are translated at the national level;

- Development of human rights systematic monitoring systems at country level, based both on the guidelines of the III National Human Rights Program (PNDH3) and the UPR recommendations;

- Development of consistent human rights indicators;

- Creation, by 2014, of new police stations to effectively respond to gender based violence.

Civil society organizations present at the dialogue listed other measures to also be prioritized as a result of the second UPR round, such as:

- Establishment of an independent national human rights mechanism, as it has been systematic recommended since 2008;

- Systematic and transparent dissemination of information on human rights violations occurring at country level;

- Conducting a public hearing at the Brazilian Congress, to ensure that the recommendations made to allowing for civil society to participate in the discussion of what recommendations were to be rejected or accepted.

It must be said, however, that the dialogue that began in Geneva regarding these various proposals and themes has not continued, as expected, at country level. Several Brazilian NGOs responded to the recommendations made by member states, writing letters to Brazilian authorities and the diplomatic missions that had made them. However, the public hearing scheduled for August to discuss the recommendations presented to Brazil has been cancelled and, in result, the Brazilian government reacted to the recommendations, without having properly consulted with civil society organizations directly engaged in the UPR process. A second public hearing scheduled for October, now to discuss the UPR process as a whole, was also indefinitely postponed. In both cases, the cancellation was justified by the lack of quorum at the House of Representatives, due to municipal elections of which the first round was on October 7th). The good Brazilian performance in Geneva does not imply, therefore, that national institutions are thoroughly informed and committed to the process, or that the recommendations made will be effectively translated at the country level. The UPR cannot be seen and responded to as an isolated event. The review is one necessary, but also insufficient step in the context of broader efforts required to effectively enhance a culture of human rights — there including sexual and reproductive rights — in Brazil. For such a culture to continue flourishing it is vital to keep identifying and denouncing violations, expanding information and knowledge about national and international human rights institutions, and also to improve civil society means and technical capacity to establish systematic connections with the transnational channels through which human rights claims presently flow.

________________________________________________________________________

*SPW thanks Magaly Pazello, from EMERGE-Communication and Emergence Research Centre and Women’s Networking Support Programme of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC), for the attention giving information and details on the second round of the Brazilian UPR and sharing her analysis and observations on this process.